March 20, 2024

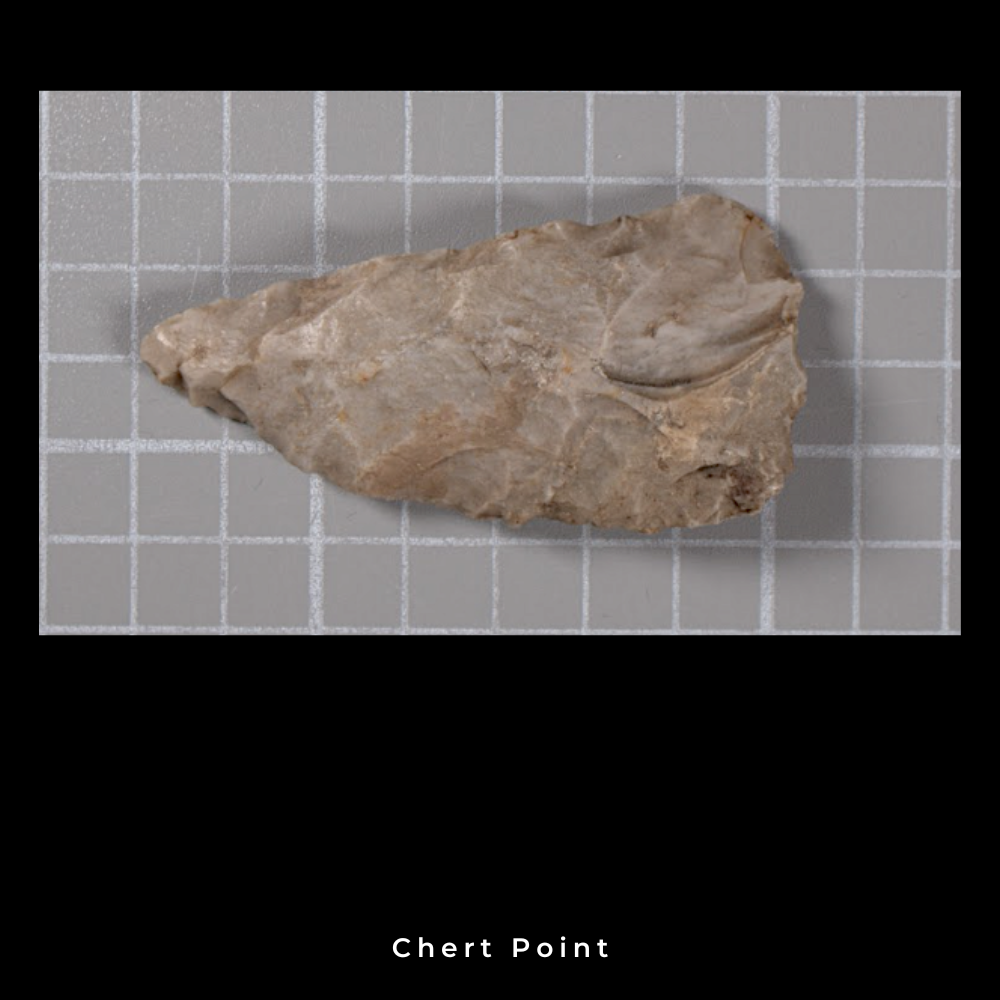

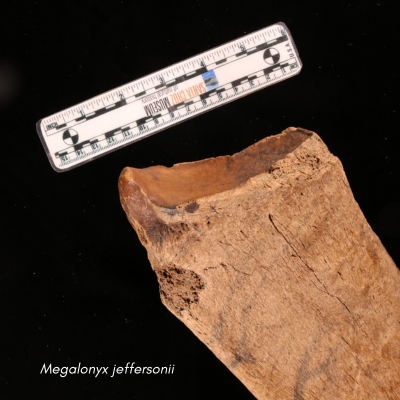

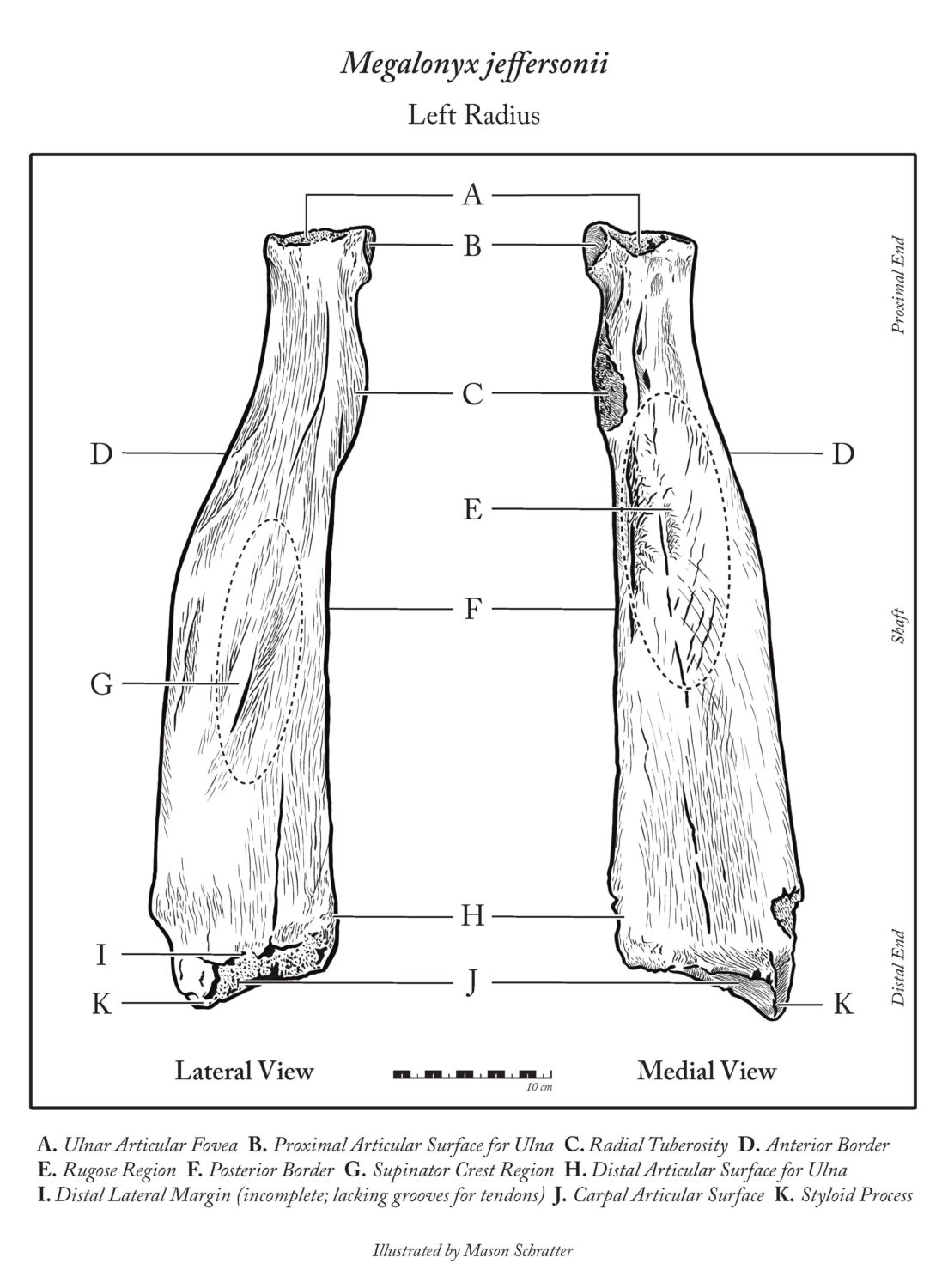

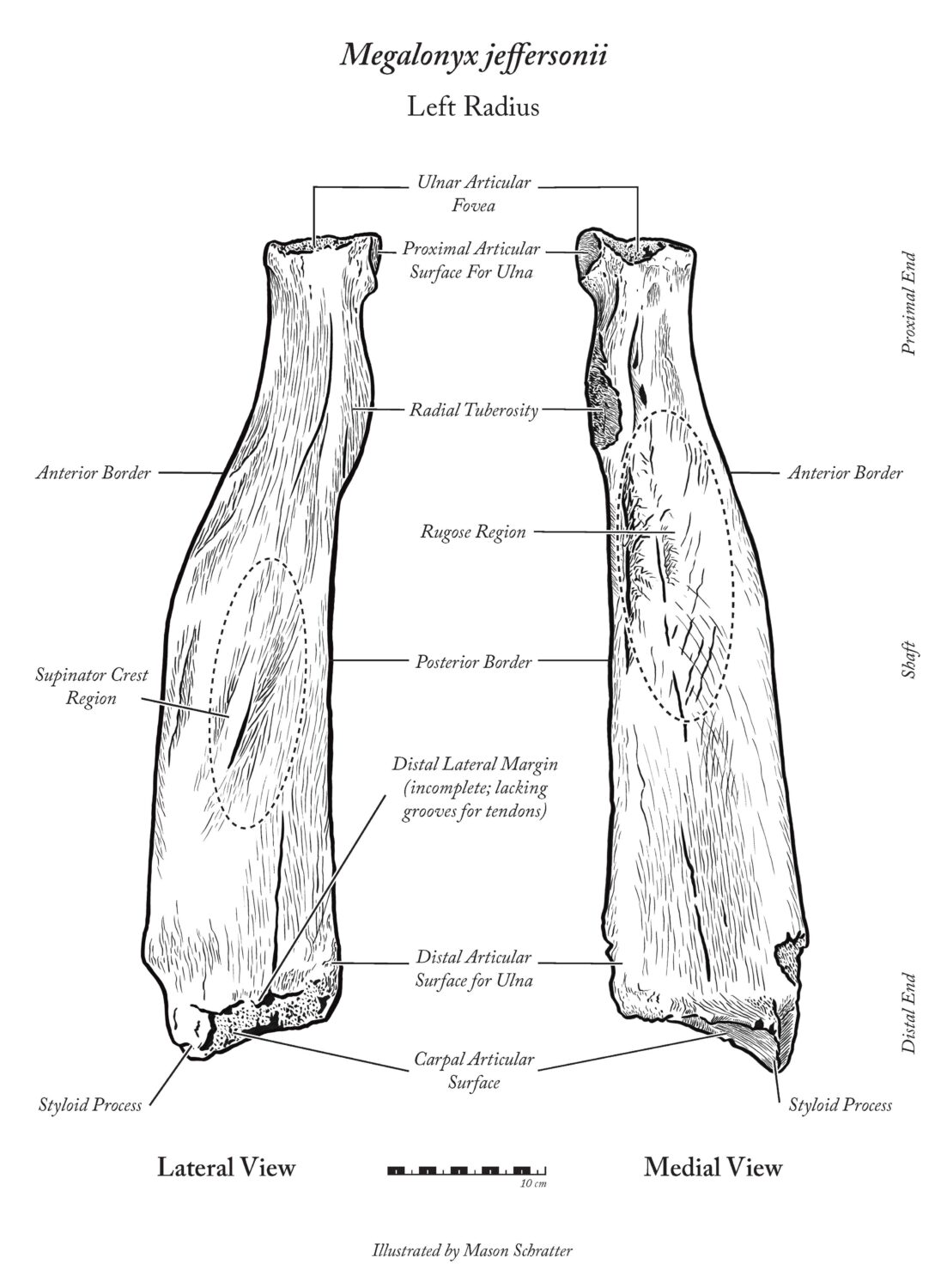

Local students from Tara Redwood School playing in a Santa Cruz Mountains creek last spring found a strange object that they suspected was a bone from a large animal. This bone was brought to the Santa Cruz Museum of Natural History where their Paleontology Collections Advisor, Wayne Thompson, recognized it as a fossil arm bone (left radius), likely belonging to an ancient sloth. Thompson called in fossil sloth experts who confirmed that this bone came from a Jefferson’s ground sloth (Megalonyx jeffersonii), making this specimen the first reported fossil evidence for this species in Santa Cruz County.

“Megalonyx jeffersonii is one of the very first fossils documented in North America – it’s just one of those iconic animals that more people should know about,” states ground sloth expert Melissa Macias on the importance of this discovery.

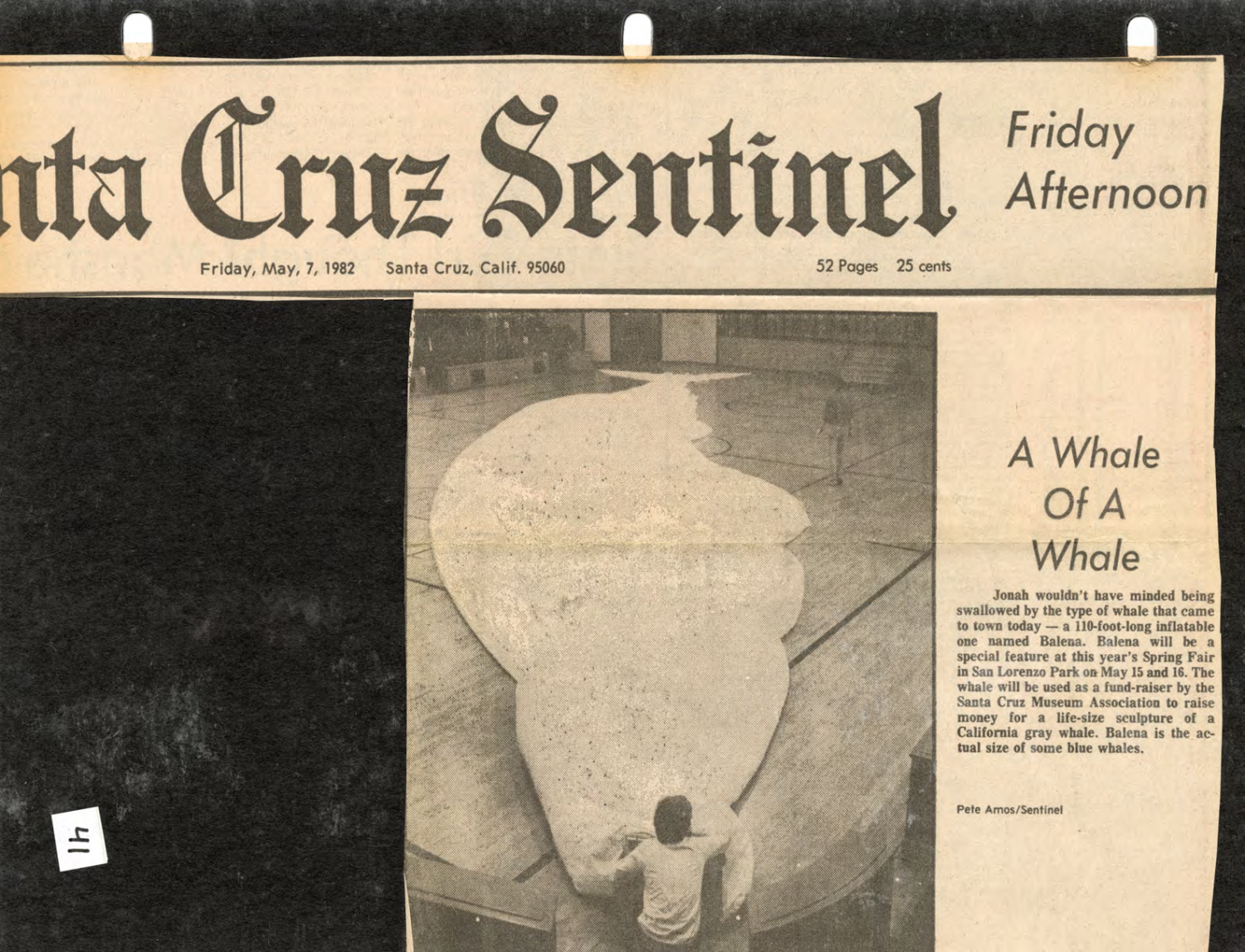

The Museum of Natural History is currently working with local scientists to determine whether it is possible to come up with a precise age for this specimen. In the meantime, they know it was found in an Ice Age river bank deposit, placing it in a ballpark of between 11,500 years and 300,000 years old. This find follows on the heels of the mastodon tooth that was discovered on Rio Del Mar beach in 2023. Both of these fossils are from a similar era and their discoveries increase our understanding of what this region would have looked like in the Pleistocene.

“Fossils are a great way to engage people with the deep past,” said Felicia Van Stolk, the Museum’s Executive Director, “and we’re so excited students made this important discovery that will continue to inspire generations of museum visitors and scientists.”

About Megalonyx jeffersonii

1. What is a sloth ?

Sloths are members of a group of mammals called Xenarthrans. The name Xenarthran comes from ancient Greek words meaning “strange” and “joint”, which refers to the unusual and unique shape of these animals’ vertebral joints. They are closely related to anteaters and armadillos.

2. Comparison with modern sloths

Ground sloths are distant cousins of today’s modern sloths inhabiting central and south America. The two modern groups of tree-dwelling sloths evolved independently from land-dwelling ancestors.

3. What is Jefferson’s ground sloth ?

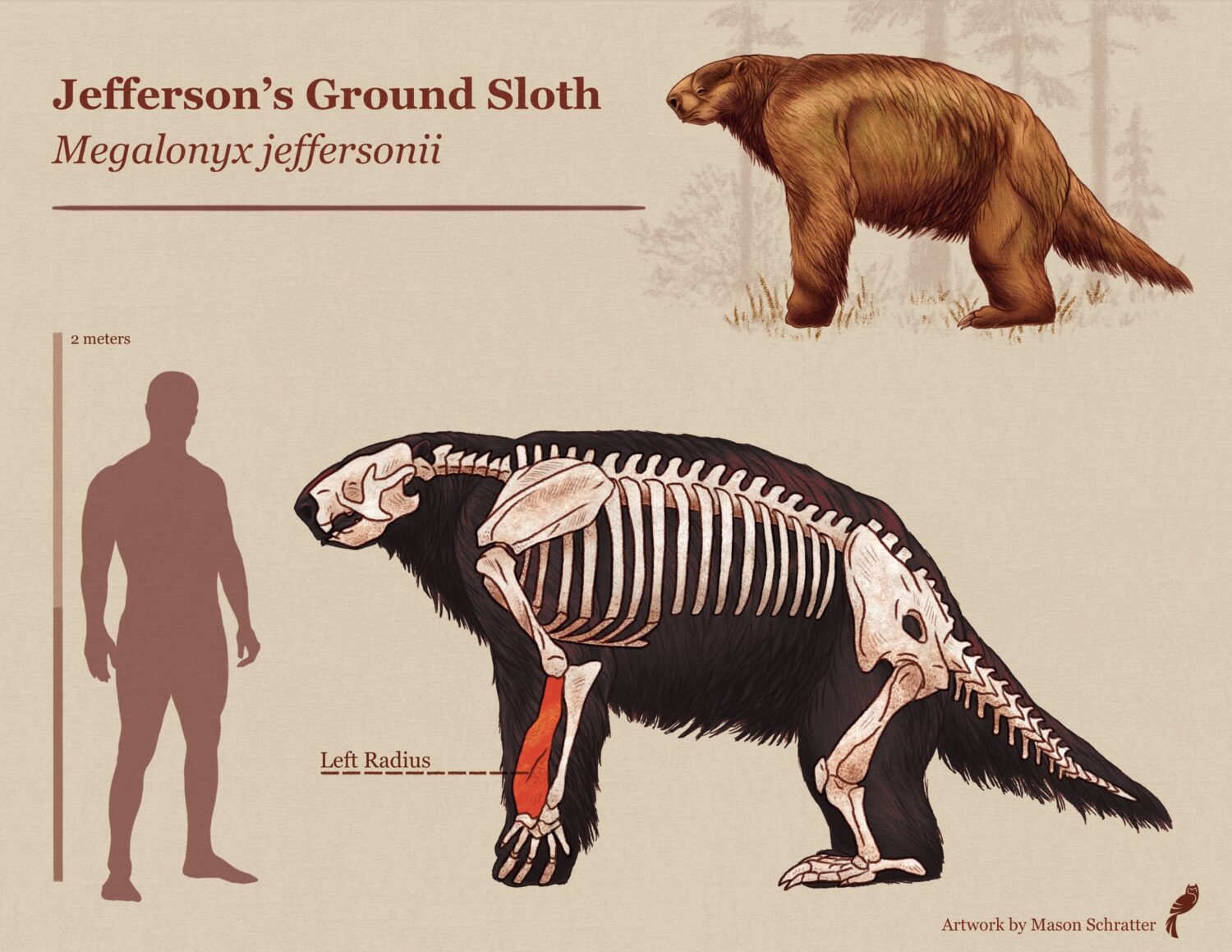

Jefferson’s ground sloths were large herbivorous mammals with blunt snouts that roamed the earth in the past. Comparable to an ox in size, they could grow up to three meters long and weigh between 2200 and 2425 lbs. They inhabited woodlands and forests near rivers and lakes, using their long, sharp claws to forage for food, such as stripping leaves from branches. They were capable of walking on all fours as well as standing on their hind legs, and used caves for shelter.

4. The origin of its name

The term ‘Megalonyx’ is Greek for ‘great claw’, describing the distinctive claws of sloths in this genus. The species name ‘jeffersonii’ pays homage to Thomas Jefferson who presented a scientific paper on Megalonyx to the American Philosophical Society in 1797, marking the dawn of vertebrate paleontology in North America.

5. When did ground sloths inhabit the Earth?

Megalonyx is part of a family group of sloths that appears to have emerged in South America about 30 million years ago, migrating onto the North American continent as early as 8 million years ago by crossing the Isthmus of Panama Land Bridge. Several species of ground sloths were found across North and South America during the Ice Age, during which time they were sometimes hunted by Indigenous people who shared the landscape with these mega mammals.

Jefferson’s ground sloth remains are commonly found in the western United States, the Great Lakes region, and Florida, but specimens of this species from California are rare. They went extinct around 11,000 years ago and scientists are still investigating the cause of their extinction.

6. What was the Jefferson ground sloth’s habitat?

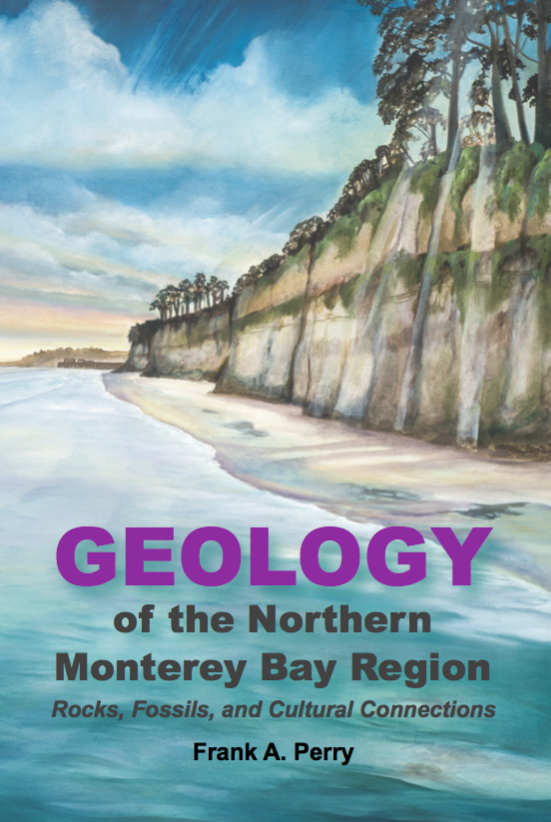

Jefferson’s ground sloth lived in cool, wet, spruce-dominated forests in riparian settings and gallery forests associated with rivers, much like the American Mastodon, Mammut americanum.

7. Presence of sloths in the SF-Monterey bay areas

The remains of Megalonyx jeffersonii are rarely found in California, with a higher concentration of findings in Shasta County and Los Angeles County. This specimen marks the first confirmed ground sloth discovery in Santa Cruz County and is one of the few confirmed specimens in California.

Today’s rainforest sloths are very different in size and look from the ancient ground sloth.

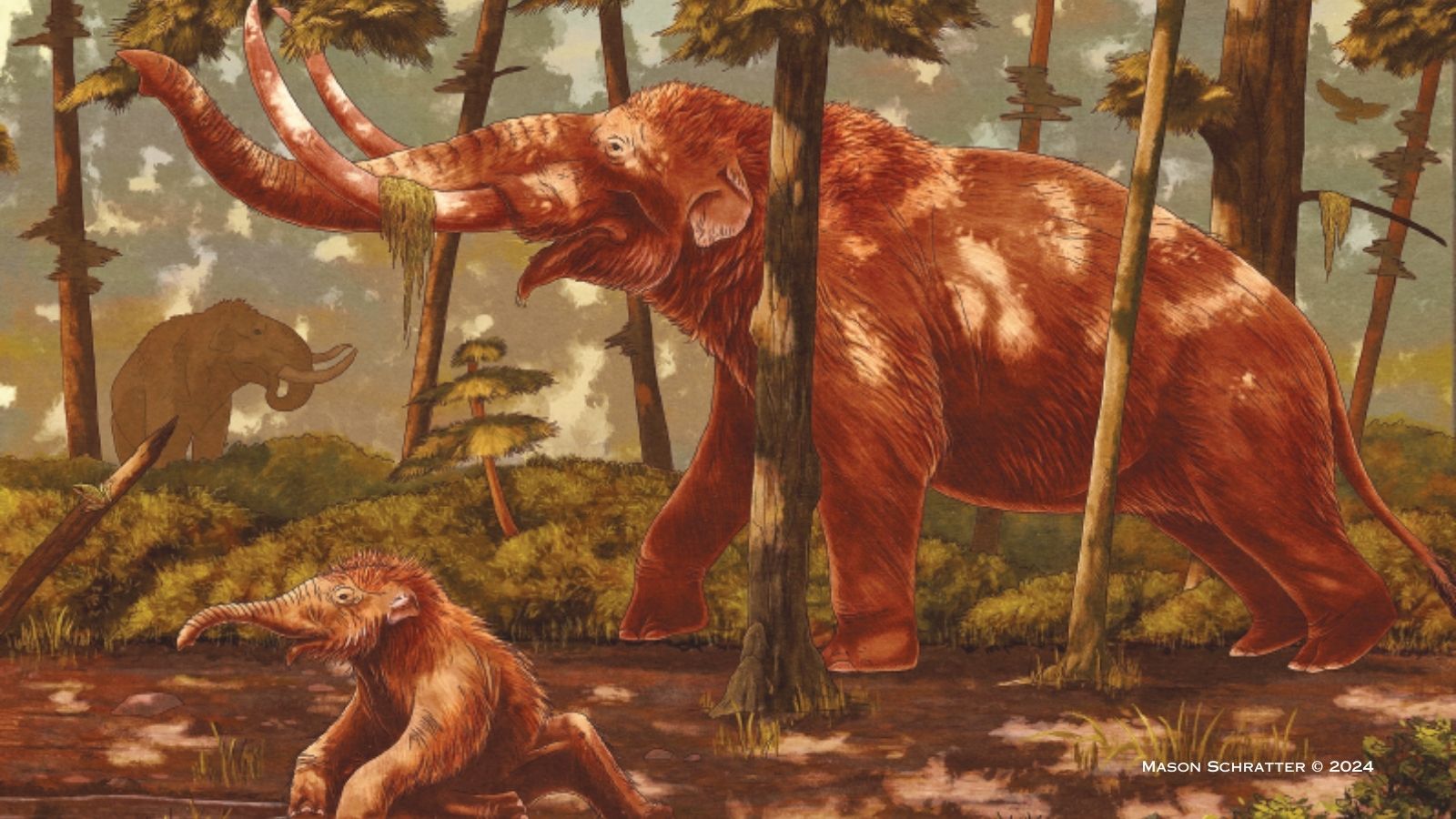

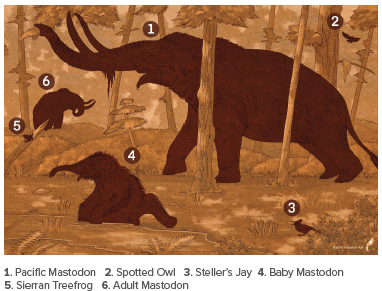

Artwork by Mason Schratter

Wayne Thompson, Paleontology advisor for the Museum’s collection

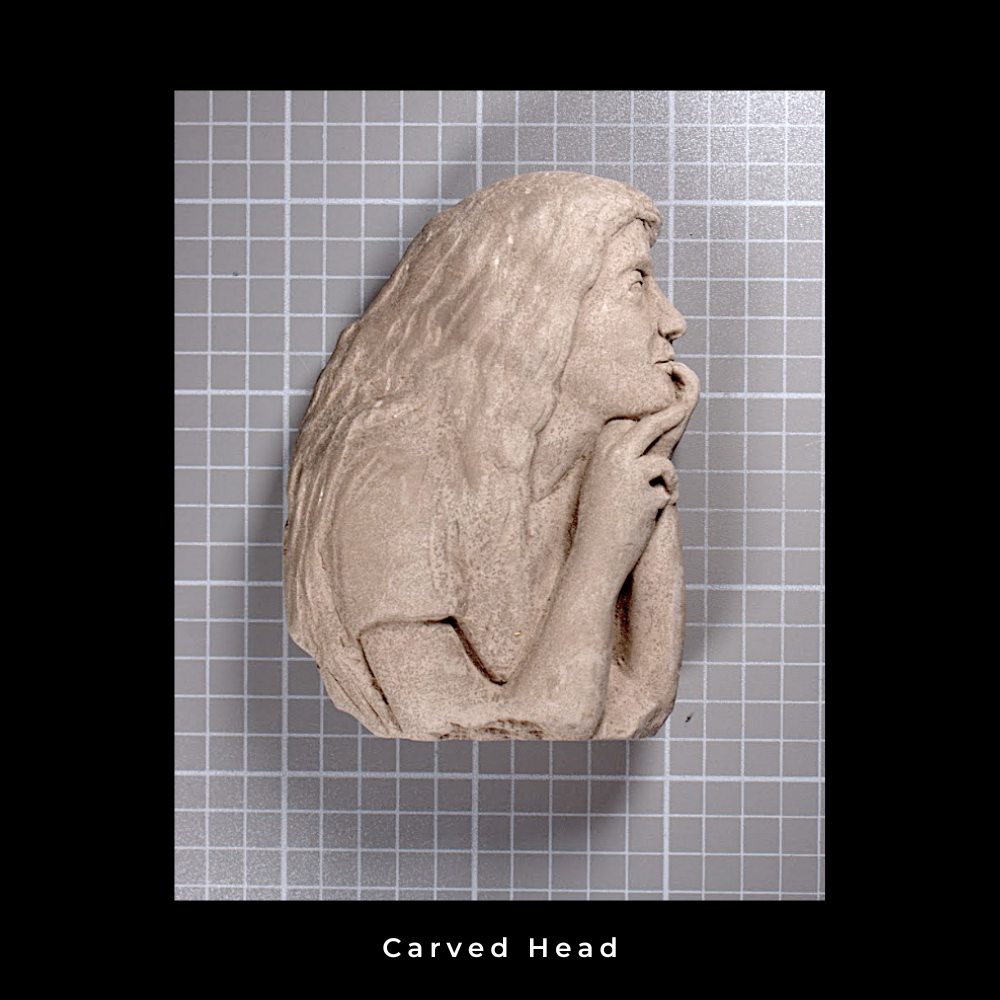

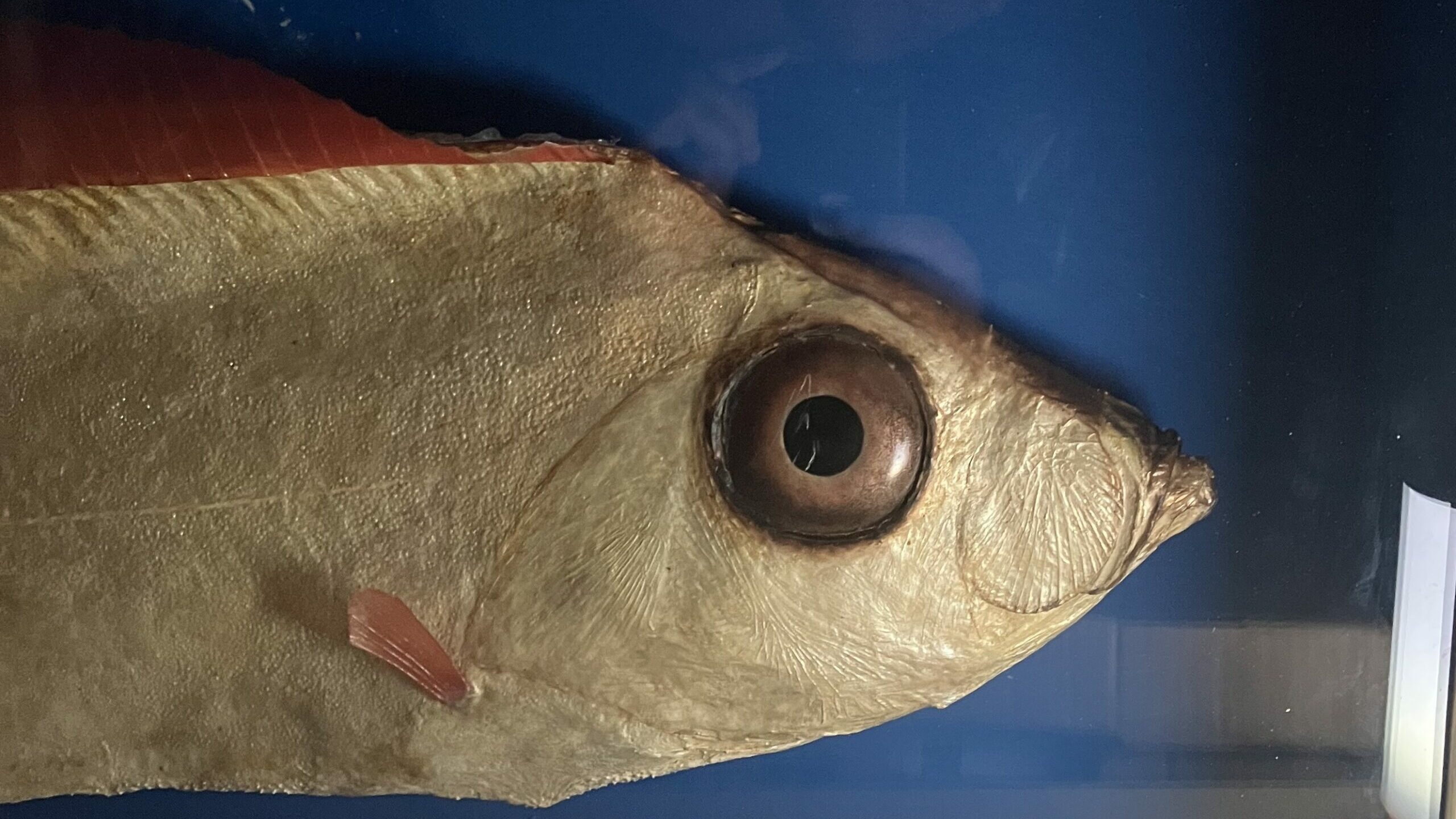

3-D image scan of the Jefferson sloth bone at the Santa Cruz Museum of Natural History

3-D image video from Wayne Thompson, Paleontology Advisor for the Museum

Jefferson’s ground sloths are large, extinct, plant-eating mammals with blunt snouts. At full size they were about the size of an ox, up to three meters long and 2200-2425 lbs. They mostly lived alongside rivers and lakes in woodlands and forests, and their long sharp claws were probably used for grasping at food, such as stripping leaves from branches. These three-fingered sloths walked on all fours but could stand on their hind legs, and some used caves for shelter.

Artwork by Mason Schratter

The Museum worked with local science illustrator Mason Schratter to bring this species back to life in a gorgeous depiction of Santa Cruz in the Pleistocene. This artwork will be exhibited alongside the fossil in the Museum’s annual exhibit of science illustration, The Art of Nature, open March 23- May 26, 2024. After the exhibit, the fossil will be carefully stored in the Museum’s collection where it will be accessible for research and future publication.

Ethics of Collecting

- Always know before you go when collecting.

- Determine whose property you are on and what their rules are for collecting.

- Generally, collecting fossils is not allowed on most public land.

Fast Facts

- The fossil bone is a left radius found in Santa Cruz County

- The species is Megalonyx jeffersonii, Jefferson’s ground sloth

- Dates 11,500 – 300,000 years old, from the Pleistocene Era

- On exhibit March 23 – May 26, 2024

For more information, check out our guide to collecting fossils