A natural history museum collection is as much a collection of methods as it is a collection of objects. We learn a lot by looking at these forms of collection, and we benefit from the many local individuals who have contributed their personal materials, their eye for detail, and their passion for the natural world to our museum. Oftentimes our artifacts and specimens connect us to the broader stages of science and history, whether it be our founder Laura Hecox’s correspondence with a Midwestern scientist or the Smithsonian borrowing materials from our ethnographic collections. In our entomology collections, we find specimens that not only represent entomological diversity but also connect us to the history of a natural sciences institution that has played a major role in science education for years: Ward’s Natural Science Establishment.

Ward’s Natural Science Establishment was founded in 1862 by 28 year-old Henry Augustus Ward. Ward was a lifelong student and enthusiast of the natural world, having begun his first collection, a set of geology specimens, at the age of 3. As a young man he took off from the States to travel the globe, gathering specimens all the while. He would even sell fossils he collected to further finance his education in geology. This entrepreneurial spirit served him well, and led to the collection commissions that provided the foundation for Ward’s Natural Science Establishment. Notable collection endeavors include Ward’s stunning fossil, mineral and meteorite display at the 1893 World’s Fair, which was purchased by Marshall Field and donated to what would become the Field Museum in Chicago. During their heydey as a museum’s collections supplier, which lasted through the early 1940s, Ward’s employed many scientists to collect, identify, and prepare their specimens.

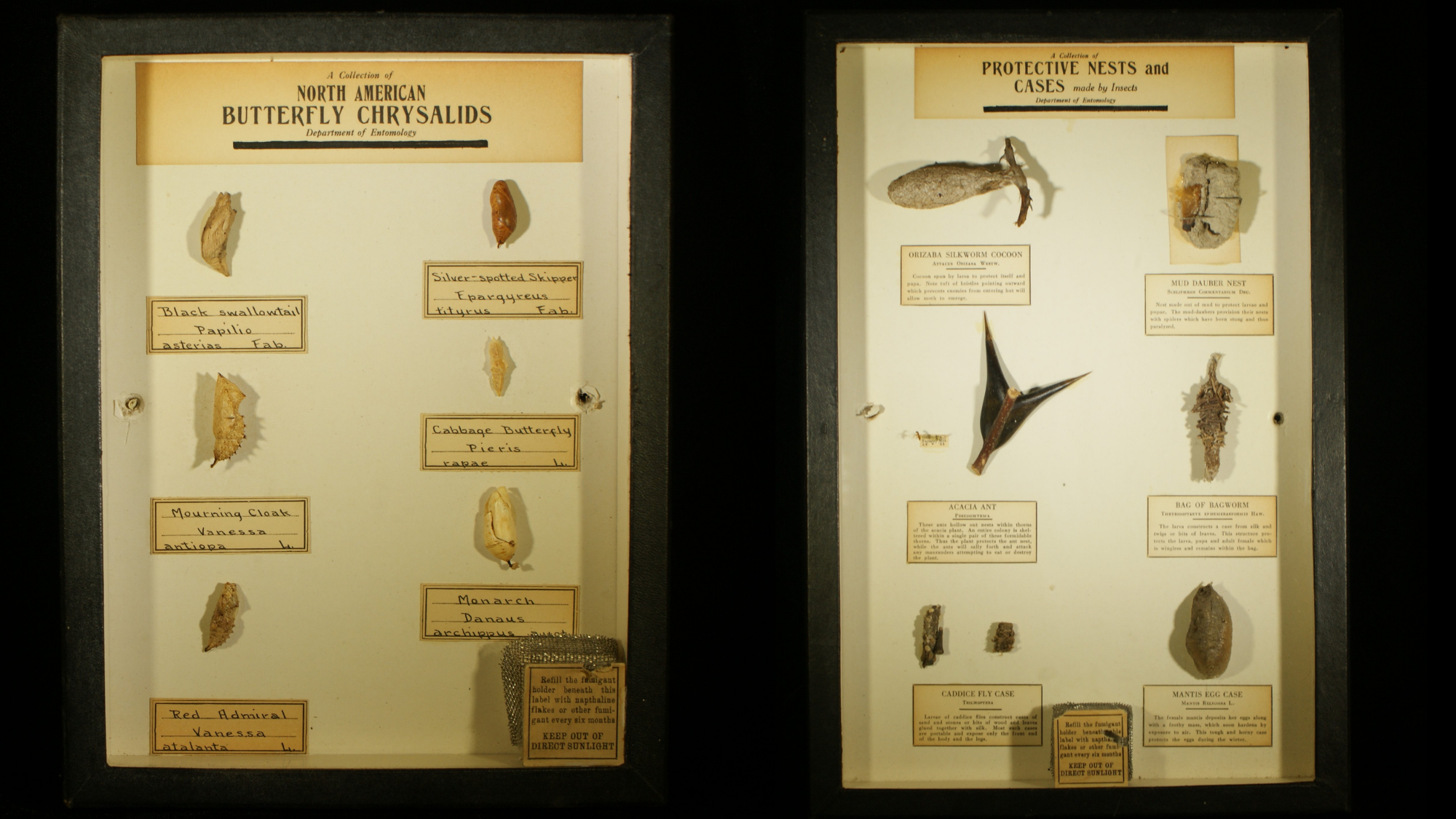

While Ward’s was historically known as a premier purveyor of fossils and minerals, their collections products extended into all branches of natural history, including the entomological displays that are this month’s Collections Close-up. Purchased from Ward’s in the 1930s, we’re looking at two displays: “North American Butterfly Chrysalids” includes a chrysalis each of Black Swallowtail, Silver-spotted Skipper, Mourning Cloak, Cabbage, Red Admiral, and Monarch Butterflies. These specimens represent the third stage of the butterfly life cycle, at which point the fully grown caterpillar sheds its exoskeleton to reveal the chrysalis, or pupa, which then hardens to provide a protective shell within which its body will undergo metamorphosis into a butterfly. This stage can last for a few days or up to a year depending on the species.

Our other feature is the display “Protective Nests and Cases made by Insects,” featuring the Orizaba Silkmoth cocoon, Mud Dauber nest, Bagworm bag, Caddisfly case, Mantis egg case, and Acacia Ant with hollowed out thorn. These specimens show greater variance, in that some are cases insects produce whereas others are natural elements insects utilize, and they also show the change in naming, both common and scientific, that can occur as our understandings of insects change: the “orizaba silkworm cocoon, Attacus orizaba” is now referred to as the Orizaba Silkmoth, Rothschildia orizaba.

Alongside their product catalogs, Ward’s also produced bulletins and guides, such as “How to make an insect collection.” Containing a range of information on capturing, breeding, and preparing specimens, the book reflects the company’s overall interest in educating people to do good science: “A job worth doing at all is worth doing well, and a scientific collection of insects cannot be obtained unless certain fundamental methods are followed.” You can find this guide through the Biodiversity Heritage Library repository of digitized biodiversity texts.

Over the years Ward’s Natural Science Establishment has transitioned from primarily serving the collections needs of the museum industry to Ward’s Science, serving the classroom needs of schools and colleges and offering everything from classic educational specimens to AP science activities. Nonetheless, Henry Ward’s passion for engaging natural materials in public displays lives on in museum collections far and wide, from fossils in the Field Museum to chrysalids here in the Santa Cruz Museum of Natural History.