Seabright State Beach has been a popular spot for more than 100 years, providing cool coastal relief from the valley’s hot summers and fun for visitors and residents alike. It’s also a picturesque meeting of the forces of nature and civilization, where the two vie for the shaping of place. For many of those years, this sandy cove at the end of Seabright Avenue was known as Castle Beach.

The name was inspired by the Scholl Mar Castle — a structure that once stood across from the Museum at the beach’s entrance — and it is the unifying element of the Bob Watson Scholl Mar Castle Collection, which we’ll explore today. This collection is a recent gift from a family member of the castle builders, and consists of historical photographs and ephemera. These artifacts expand our understanding of the Seabright community in which we are deeply rooted, while allowing us to observe and explore changes in the natural world over time.

Though it was a popular spot, Seabright’s beach often narrowed for much of the winter. What shore remained was famously packed with driftwood. In Reminiscences of Seabright community bastion Elizabeth Forbes’ turn of the 19th century memoir, the author recalls, “The coming in of the driftwood on the Seabright beach has always been one of the great excitements of the winter. I have seen several hundred cord on the beach at once.”

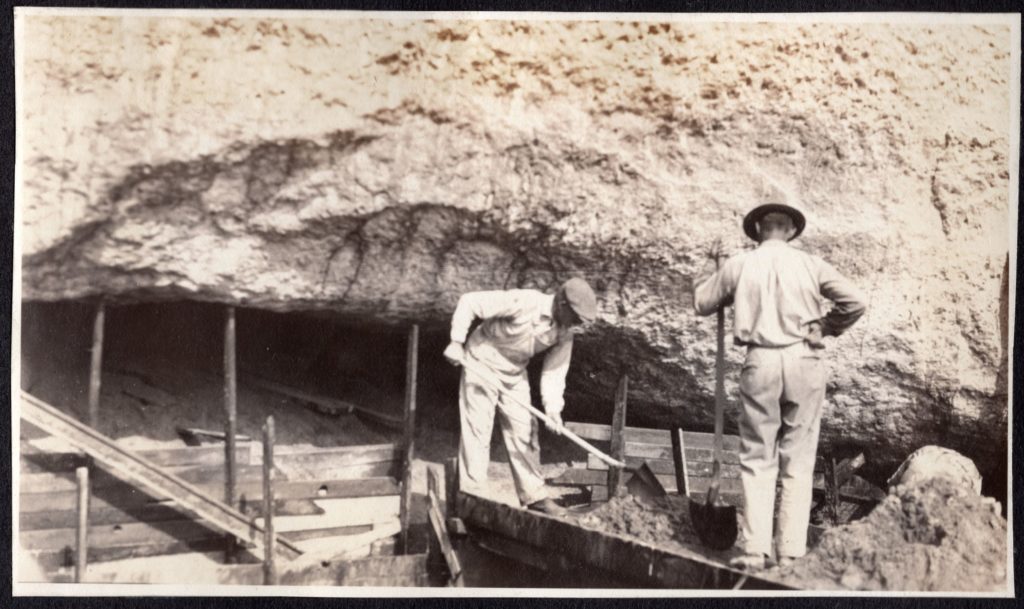

Even years later, as the image above shows, the very men who built the castle stood amidst a beach overrun by driftwood. Locals harvested the wood for various uses, from bonfires to heating baths, though today collecting driftwood is regulated by the California Department of Parks and Recreation.

In part because Seabright Cove tended to gather the widest amount of beach on this stretch of coast, it was here that James Pilkington built a saltwater bathhouse in 1903. James was the cousin of foundational museum collector Humphrey Pilkington. In 1918, father and son duo Conrad and Louis Scholl took over the bathhouse, adding a candy shop and restaurant several years before the building was transformed into the castle.

It was a family affair, and Louis’ sister Gladys spent years managing the bathhouse and renting swimsuits. During these years her son, Bob Watson, who donated this collection, grew up exploring Seabright. It was also during these years that young Bob witnessed, alongside the rest of the community, the 1929 refashioning of the business into the Scholl Mar Castle. Its reception was positive and, indeed, the collection includes a letter from then-mayor Fred Swanton acclaiming the change.

“I wish to congratulate you and the Seabright residents upon the wonderful and permanent improvement you have made on your beach property,” he wrote. “The transformation in your bathing pavilion is fine.”

As mighty as the castle was, Louis Scholl still spent a great deal of effort shoring it up against wild waves. Crashing logs battered the foundation. Storms sometimes broke windows.

Louis sold the Castle in 1944, making way for a handful of different businesses. But the castle’s ultimate removal in the wake of a damaging fire took great effort. Margaret Koch, writing for the Sentinel in March of 1967, eulogized “…enough of the old under-structure held to make it necessary to get two bulldozers on the job. They pushed and puffed and snorted and the stubborn old building finally came crashing down.”

While there are certainly still storms and seasonal changes in our beach’s shape, perhaps one of the biggest shifts in Castle Beach happened as a result of the construction of the 1964 Santa Cruz Small Craft Harbor. The harbor’s west jetty, where Walton Lighthouse sits today, traps sand that fends off eroding waves from the Monterey Bay and accumulates to make more space for sunbathing and sand castles.

Conversely, the construction had a narrowing effect on nearby Capitola Beach, as sand that would have otherwise traveled down to the coast did not make it past the harbor jetties. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built the 250-foot breakwater and trucked in roughly 2,000 truckloads of sand in 1969, and Capitola regained its beach.

Collections like these help us to understand our place on the coast, especially in an era of changing climate and coastlines. We’re eager to dive deeper in this collection as we prepare for an exhibit on the Scholl Mar Castle Collection next summer.

As we learn about the past, we are fortunate to have a rich community of local resources, such as Gary Griggs and Deepika Shrestha Ross’ Then & Now book on the Santa Cruz Coast, or Randall Brown and Traci Bliss’s Santa Cruz’s Seabright. Here in the present, you can snag a copy of these great beach reads from our giftshop when you stop by the Museum this July to see firsthand these rich photographs of changing and changeable coast.