Sometimes nature can feel distant. As we move through the obligations and opportunities of everyday life, it can be hard to see the way that the natural world shapes the things we do and see. At other times, we can’t help it. Like when you finally have time to take that walk in the woods, or when you’re awakened by an earthquake, or your hair is tousled by the wind. Or, when someone is using nature to make a point.

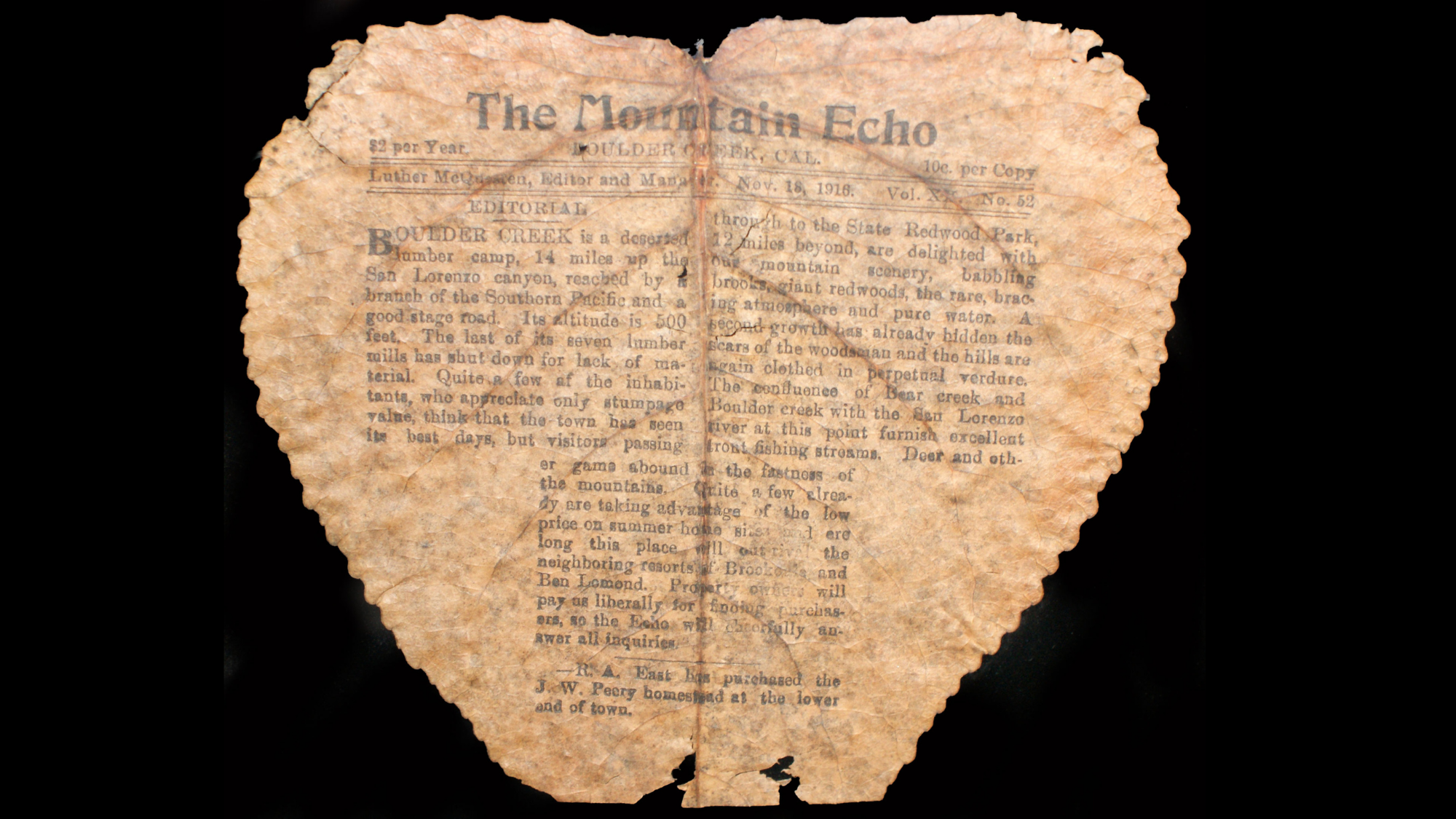

One such example is this month’s Collections Close-Up: a newspaper issue printed, not on paper, but on the leaf of a tree picked in the Santa Cruz Mountains one hundred and three years ago this November.

In 1916 newspapers were embattled by the high cost of paper. This was due in part to supply shortages caused by World War One, which were aggravated by a widespread increase in publication demand. Closer to home, the relatively new publisher of Boulder Creek’s Mountain Echo paper had another problem: his readers weren’t paying their fees.

To drive home the stark realities of the situation, Luther McQuesten printed four issues of his paper on leaves! A contemporary article from the American Printer and Lithographer ties McQuesten’s strategy to the changing of the seasons: “The advent of fall gave him an idea, and he gathered a bale of golden cottonwood leaves, which are broad and smooth and the Mountain Echo began echoing on Nature’s own papyrus.”

Although now faded from gold to brown, this November 18th, 1916 issue still carries the news of the day. An editorial extols the virtues of Boulder Creek’s beautiful trees and babbling brooks, local families have visitors, a Winchester rifle is for sale, and D.E. French is visiting again to enjoy the scenery and collect specimens of native woods.

The leaves proved sturdy, and our collection is not the only one that stewards one of these remarkable issues. The Boulder Creek Branch of the Santa Cruz Public Libraries has some copies on display, and the San Lorenzo Valley Museum has some in their collection as well. In fact, the San Lorenzo Valley Museum houses the original copies of the Boulder Creek Mountain Echo newspaper, both those made with “nature’s own papyrus” as well as plain old wood pulp.

We reached out to SLV Museum Board President, Lisa Robinson, to learn more about this unique object. Lisa is a wealth of knowledge, especially when it comes to the Santa Cruz Mountains. She has also authored the “Redwood Logging and Conservation in the Santa Cruz Mountains: A Split History,” among other things.

Lest you think this leaf printing was a tired gimmick, Lisa told us that in all her years of working in museums and historical collections, she hasn’t encountered anything like this object. She highlights the technical feat of being able to print legibly on both sides of the fragile leaf. McQuesten was fully committed to people actually being able to read these nature notes – an attitude underscored by the fact that the newspaper subsequently reprinted the content of each issue on regular paper. While we don’t know exactly which of the newspapers’ presses was used for this printing, one of them still exists and is now at San Francisco’s Book Club of California.

In this image from the SLV Museum’s collections you can see the Mountain Echo office at the corner of Highway 9 and Forest St, in downtown Boulder Creek. Less than a block away from the location of the former office stands a handful of cottonwood trees (Populus fremontii).

In 1917, an article from the Santa Cruz Evening News described the printed leaves as having brought McQuesten a “vast amount of desirable publicity” from all over the United States. Despite this notoriety, McQuestion’s stunt didn’t appear to have its desired effect: the Mountain Echo ceased publication shortly afterwards. And while the Mountain Echo is no longer covering local news nor nagging delinquent subscribers, this page of “nature’s papyrus” persists. It will be on display all this month in the Museum’s Collections Close Up, highlighting the contrast between nature we think of as natural, and the items from nature we use everyday.

If you want to explore more on related topics, stop in the Museum Gift Shop to find Lisa’s book about conservation in the Santa Cruz Mountains, and on November 23, join us for a seminar on American Indian Art, made from nature’s resources.