Member Exclusive: Join Collections Manager Kathleen Aston for a special webinar on July 9 at 5:30 p.m. as she explores the specimens and stories of our malacology collection. Learn more.

“Even if there are no collectible shells, a walk along the tide drift will yield recognizable bits and pieces of fifteen to twenty species. Don’t spurn them. Half the joy in collecting is in the learning process; these imperfect pieces are valuable starters – studying them will enable us to recognize and identify the perfect specimen when we finally find it. Shells, like gold, are where you find them.”

-Hulda Hoover McLean

Thus advises Hulda Hoover McLean in her introduction to the Tide Drift Shells of the Monterey Bay Region. Originally published in 1975 as the Tide Drift Shells of the Waddell Beaches, naturalist and conservationist McLean wrote the book in response to what she saw as a growing interest in local young people at the time in the natural features of the world around them. Her book could only further captivate them. The identification guide reads as an informative yet personal story – grounded as it is in a lifetime of collecting shells of all kinds (and levels of completeness!) on the shores of the Monterey Bay.

Enthusiastic gratitude towards scientific advisers is balanced by wry encouragement not to bother professionals with amateur questions unless absolutely necessary; antique quotes describing the richness of local mollusk diversity are displayed opposite sorrowful personal observations on the diminished number of shells available today; the pageantry of tidepool creatures is lauded while the “horror” of shell art and crafts is disparaged. Organized by scientific class and family, the standard identifications for these shells are enhanced by local context and practical notes.

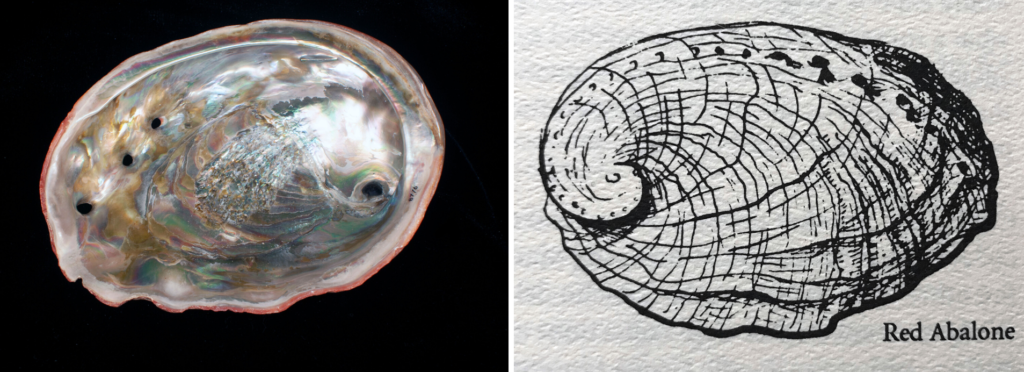

Red abalone (Haliotis rufescens), is pictured here both in the book’s illustration and as a specimen from the Museum’s collection. Hulda notes that abalones have “an almost flamboyant beauty with their graceful shape and brilliantly opalescent interior.” In addition to their distinguishing identification information, McLean places the various locally found abalone species into the context of their conservation restrictions (now increased) as well as local fishing and aquaculture projects.

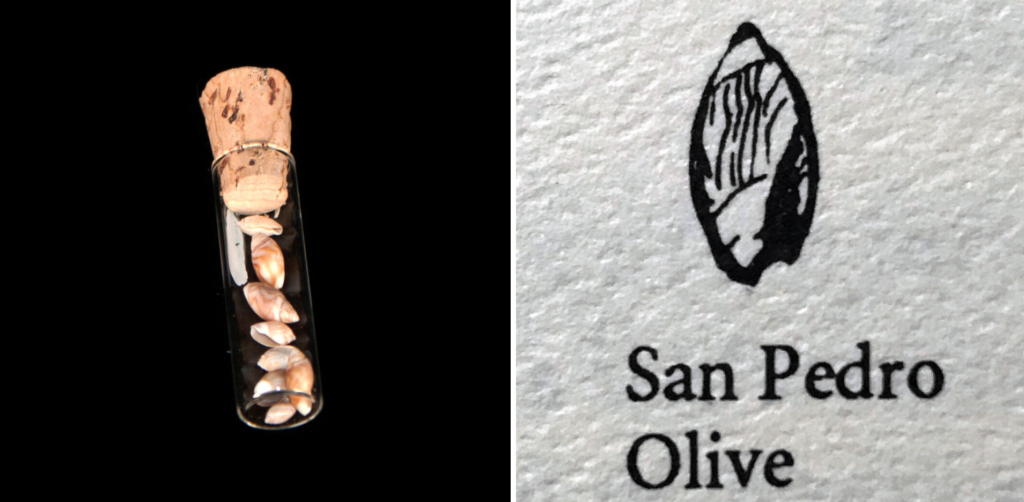

Average sizes are given for each specimen, like the 10 mm San Pedro Olives (Olivella strigata) pictured here. Often with the smaller shells, Hulda advises the potentially overwhelmed sheller to simply gather up a handful of gravel and save the task of differentiating these tiny beauties for a rainy day, the comfort of an armchair and the aid of a magnifying glass.

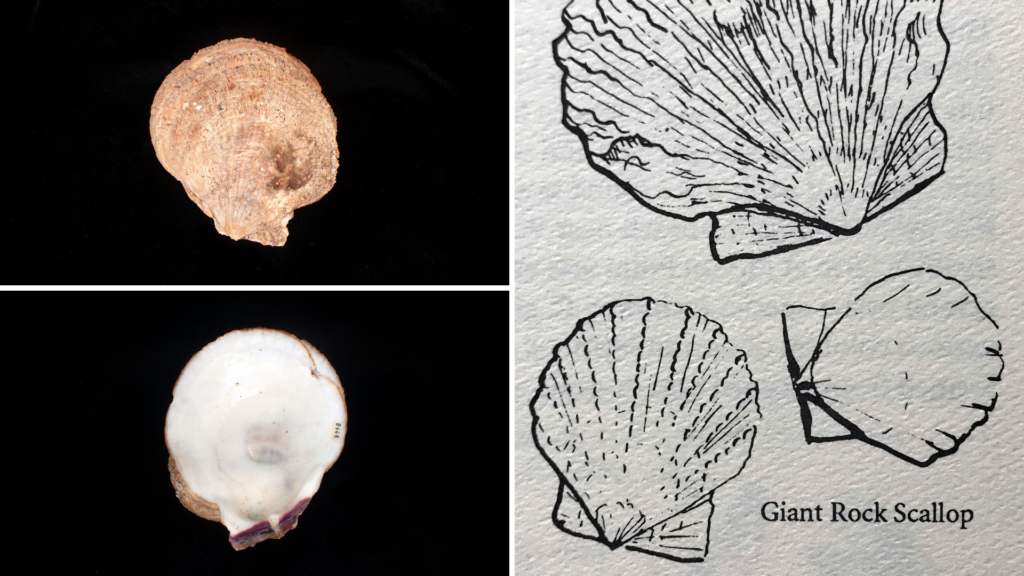

The Giant Rock Scallop (Hinnites giganteus) life cycle is described in some detail, to explain to readers the stark distinction in the forms in which they may find it – small and light colored when found from its free-swimming stage, large rough and misshapen if one finds and older specimen that had already cemented to a rock. In either case, the specimen is distinguishable by the characteristic purple stain on its hinge, seen here in the specimen rather than the illustration. Hulda herself noted the value of color photographs, and mentions in her introduction how she exaggerates some aspects of the illustrations in order to aid in identification of subtle characteristics.

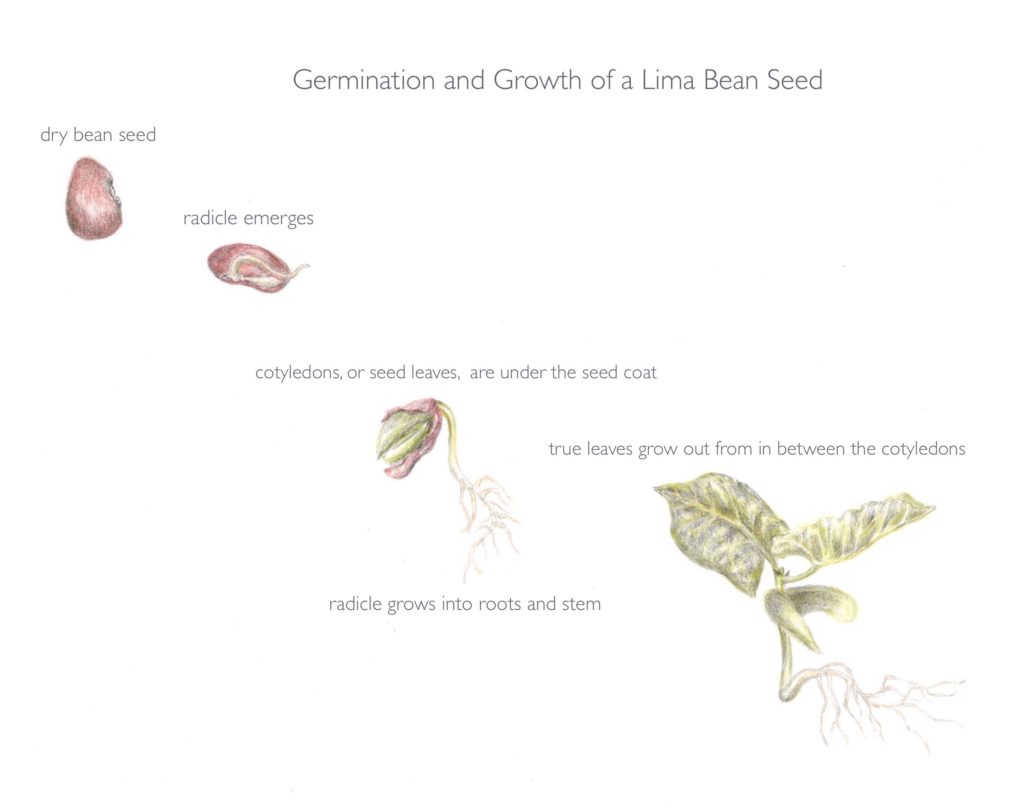

Hulda’s illustrative and descriptive styles were carefully attended to in the 1992 republishing of her book. A collaboration with the Waddell Creek Association, the original book was expanded to reflect the broader Monterey Bay Region. Several new drawings were made by Amey Mathews, the granddaughter of longtime board members/volunteers Pat and Kirk Smith. A high school student taking college level botanical illustration classes, Amey went on to study art at Stanford. A yoga teacher today, she relies on some of the same artistic skills that governed her earlier practice: observation, metaphor, and creativity. Additional descriptions, and a list of additional resources were provided by longtime Museum community member and research associate Frank Perry.

Perry has always been a great admirer of Hulda Hoover McLean. An accomplished naturalist himself, Perry admired the breadth of McLean’s knowledge of the natural world, from insects to birds, from mammals to malacology. McLean grew up roaming the family property that is now the Rancho del Oso portion of Big Basin State Park. The transfer of those lands to the state park system are largely due to her desire to see the beauty of its flora and fauna preserved for the public and posterity. “If there was a ‘Santa Cruz Naturalists Hall of Fame’” Perry says,”she would be in it.”

Perry is also a lifelong admirer of seashells – beginning childhood collections and continuing on into his work as an adult. As a paleontologist, he finds that broken shells often have more interesting stories to tell, from how they were broken and by whom, to how long the shell was empty and who else might have been using it as habitat. Perry’s ability to identify mollusk species has also come in handy for local archaeology. Faced with little information on the daily lives of the lime workers who lived at what is now UCSC, Perry’s identification of abandoned shell fragments helps us understand their diet.

Indeed, the study of shells contributes broadly to our understanding of the world, from a greater understanding of the consequences of ocean acidification to the broadening of possibilities for human architecture and more. Pairing their versatile scientific contributions with amateur collections that, in McLean’s words, represent a “lifetime investment in beauty”, it is easy to see how shells are as good as gold.