By Gavin Piccione and Graham Edwards

Caves are an intersection between natural destruction and creation, where existing rocks are eroded away, and new rocks are continuously formed. Descend into one of the many caves in Santa Cruz and you’ll get a unique viewpoint of the striped marble walls that were built offshore of the area’s ancient shorelines and thrust up onto the continent over the past million years.

This geologic flux also means that one can never enter the same cave twice, since the competing geologic processes of erosion and precipitation are constantly shaping the interior. When you visit a cave, you’ll be a first-hand witness to the geologic processes that shape the Earth.

Solutional Caves and Karst

The caves of Santa Cruz are called solutional caves because they form when groundwater dissolves pathways through rock, just as sugar or salt dissolve in warm water. However, to dissolve rock, it takes more than just plain old water. Rainwater and groundwater carry dissolved carbonic acid and organic acids that are pulled out of the soil as water percolates down from the surface. In Santa Cruz the bedrock (the solid rock beneath the soil) is mostly marble and made of the mineral calcite which is very susceptible to being dissolved by weak acids like these. Thus, the slightly acidic water can easily dissolve its way into the rock.

You can try this at home or in the field! Find a piece of marble or limestone, scratch at the surface a little bit with a paperclip, key, or coin to make a powder. Drip some vinegar (which is also a weak acid) on the powder and watch it fizz as the calcite dissolves!

As rainwater and groundwater slowly dissolve their way through the marble bedrock over thousands to millions of years little cracks turn into large caves, where the many dissolved minerals such as calcite precipitate, or become solid and separate out of the liquid, forming speleothems. These water-sculpted caves have a distinctive structure and shape: smoothed and rounded marble walls filled with holes and tunnels, covered with speleothems giving most surfaces a ropey, grooved, and nodular texture. In karst systems caves can develop as we’ve described, but if they grow close enough to the surface, the caves can’t support the weight of overlying rock and they collapse forming sinkholes, a familiar feature in the Santa Cruz area.

Since karst caves are formed by flowing water, water often continues to flow into them. Especially in the rainy wintertime, caves can partially or completely fill with water, so it’s important to be very careful whenever entering or exploring caves and postpone your spelunking if it’s rainy!

Below the Surface

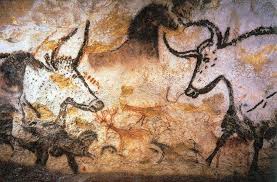

One of the most scientifically alluring aspects of caves are the preservation of rocks and artifacts that their sheltered interiors provide. Materials within caves are not subject to erosion or weathering to the extent that those exposed to the atmosphere are. Caves also stay the same temperature year-round because they are not affected by atmospheric temperature fluctuation, and instead have temperatures regulated by the ability of the surrounding rock to hold heat. These mild conditions help artifacts like the Dead Sea scrolls and cave paintings to survive for millennia. Similar to archeological preservation, rocks that would normally erode quickly at the surface of the Earth are remarkably well preserved in caves.

Caves are treasure troves of samples for geologists, biologists, hydrologists, and countless other kinds of scientists. Among the most exciting (at least for us geochronologists) are records of changing climate found in speleothems. As this calcite builds thicker and thicker speleothems, it captures the chemical signature of the climate at the time of its formation. By studying these speleothems, scientists can reconstruct the timeline of global climate change over the past 650,000 years.

Other Types of Caves

Some caves form at the same moment the rock forms, usually from cooling lava. Some examples of these volcanic caves are lava tubes — an open tunnel left behind when a subterranean conduit of lava drains. Caves can also form in the deep chasms left behind by rifts, where volcanoes split the land apart as they swell. Since lava flows, volcanoes can leave all sorts of other cave-like voids behind from the flow, storage, or drainage of lava.

Sea caves, or littoral caves, form where waves carve out deep caverns into sea cliffs, usually into weaker parts of rock. We even see a few shallow sea caves along the Santa Cruz coastline!

Anchialine caves are caverns that connect inland pools, called anchialine pools, to the ocean where the cave ends underwater. The water levels in these pools often rise and fall with the tides, and these are popular sites for scuba-spelunking!

Caves can even form above ground! Talus caves form in the spaces between large boulders at the base of rocky cliffs, and if water flows into or under a glacier, it can melt out glacial caves!

Critters in Caves

While we most often associate caves with bats, caves are home to all sorts of organisms, including fungi, arthropods (insects, spiders, scorpions, and the like), salamanders, and fish. These creatures are usually adapted to live in these perennially dark, often flooded environments. Because caves are often isolated and disconnected habitats, many creatures that live in caves are endemic, meaning they are found in that cave network and nowhere else on Earth!

For example, the Cave Gulch cave network, just North of Santa Cruz, is home to two endemic species: the spider Meta dolloff and the pseudoscorpion Fissilicreagris imperialis.

Be very conscientious when you visit caves since these are the only homes for many of the creatures that live there. Never leave trash, burn fires, or damage the interiors of caves. If you do go into caves, be sure to pack trash out, or even better, enjoy the cave from the outside and leave its subterranean residents in peace.

Rock Record is a monthly blog featuring musings on the mineral world from Gavin Piccione and Graham Edwards.

Graham Edwards and Gavin Piccione are PhD candidates in geochronology with the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at UC Santa Cruz. They also host our monthly Rockin’ Pop-Ups as “The Geology Gents”.