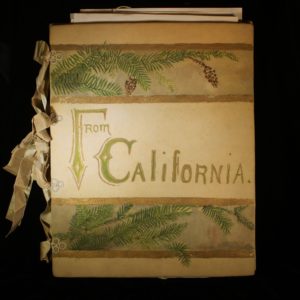

Often in the coldest months we express our warmest feelings. When remembering old friends fondly you might send an email or post a throwback photo — in the 1890s you might have dedicated a book of poems. December’s Close-Up is “From California,” a beautiful folio of poems and paintings whose cover has graced our social media pages before. This month we dive deeper!

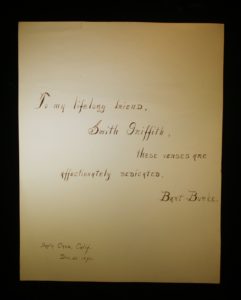

The dedication at the front of the folio announces: “To my lifelong friend, Smith Griffith, these verses are affectionately dedicated. Bart Burke Santa Cruz, Calif. Dec 20, 1890.” The author, Bartemus Burke, was born in Richmond, Indiana, and served as Santa Cruz Postmaster from 1887 to 1890. His poems, penned in fine calligraphy, speak of the joys of the Santa Cruz landscape, the delights of encountering nature and the return of wildflower season.

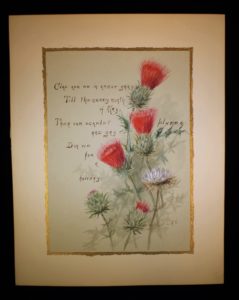

A page illustrated by the bursting reds of blooming thistles, for example, reads, “Clad are we in armor gray/Till the merry month of May/Then our scarlet plumes and gay/Don we for a holiday.” We have fewer details about Burke’s lifelong friend, Griffith. We do have a local news report, unearthed by Geoffrey Dunn in his research for Santa Cruz is in the Heart Volume II, declaring that Griffith would “not receive a souvenir of lovelier conception and design than th[is] one from Santa Cruz.”

The loveliness of this work comes not from the poems alone but from the breathtaking landscape and wildflower oil paintings that illustrate them, created by the gifted Santa Cruz artist Lillian Augusta Howard. Howard was born in 1856 and came to Santa Cruz in the early 1880s. She taught art, botany and English at Santa Cruz High, where she would later become Vice Principal.

Enchanted by the natural world, she took enrichment classes, learning how to teach students about marine plants and animals. She worked across a few mediums, including pen and ink drawings and photography. But she is best known as a watercolorist of wildflowers and landscapes.

In the late 1800s, Howard and others were fueling interest in elevating the California poppy, Eschscholzia californica, to something more than the unofficial state poppy. After holding an evening session on “Floral Culture, Wild Flowers and Ornamental Plants” at the 14th annual California State Fruit Growers’ Convention in Santa Cruz, November 1890, the flower-enamored educator opened a discussion on the proposal of a state flower.

To enhance the conversation, she showed paintings of several contenders, including the California poppy. A lively dialogue ensued, and was concluded by an impromptu vote. The California poppy won the lion’s share of votes. Formal legislature made it official in 1903.

As we wait for wildflowers to return, perhaps even the arrival California Poppy Day on April 6th, we might enjoy making a memento for a friend or loved one. If you have any special someones who would enjoy a personalized gift card or handmade nature craft, swing by our upcoming Winter Open House this weekend, Dec. 1 – 2, and dive into the holiday activities. Whether through art or exploration, with personal sentiment or historical significance, may we all enjoy the natural wonders of Santa Cruz this December!