From sea monsters, both real and imagined, to otherworldly phenomena below the surface, the ocean has long harbored frightening unknowns. Our relationship with the sea is complicated and often poses real hazards — to us and to the environment itself. As we delve deeper into the marine frontier, what mysteries and perils remain to be discovered?

Nautical Nightmares

Early mariners that ventured further and further from their homes inevitably encountered creatures that were unfamiliar and strange. Tales of these creatures traveled, giving birth to the sea monsters of myth and legend.

The ocean is vast and so are the creatures that inhabit it. Many seafarers who encountered species like blue whales, manta rays, and basking sharks had no notion of their gentle natures and instead let their fear focus on size alone.

Is it any wonder that tales of leviathans, krakens, sea serpents, and giant squid emphasize their deadly and powerful proportions?

Santa Cruz Sea Monsters

Watch: Santa Cruz Sea Monsters with Geoffrey Dunn

Geoffrey Dunn is a fourth-generation member of the Santa Cruz Italian fishing colony who grew up with stories about the “Old Man” and sea monsters as a boy, which has influenced his work as journalist, filmmaker, and historian. Watch this online talk exploring local myths and legends.

In 1925, a strange serpentine creature with a “duck beak” washed ashore at what is today Natural Bridges State Beach. Some speculated that it was a fossil plesiosaur that emerged from a melted glacier or a sea monster from the Monterey Bay. Scientists from the California Academy of Sciences collected the specimen and later identified it as a Baird’s beaked whale (Berardius bairdii).

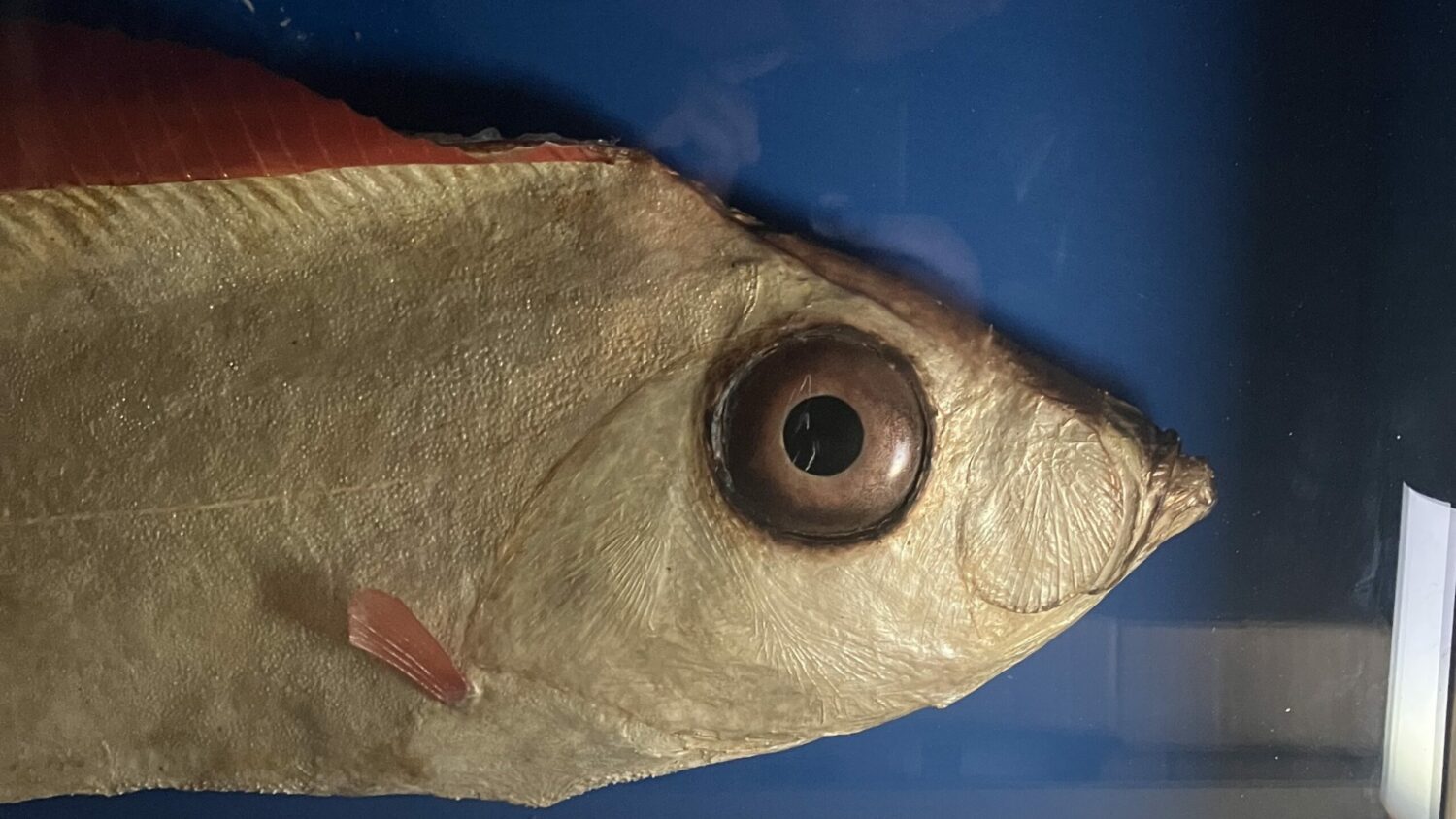

From ancient myth to these modern sightings, sea serpents persist in lore across numerous cultures. Many sea serpent stories, including local ones, likely came from sightings of rare oarfish or ribbonfish. These long, thin deep sea fish can breach the surface when they are sick or dying.

When deep sea creatures ascend to the surface or wash ashore, we are confronted with the unknown. At the height of the sardine canning industry in the 30s and 40s, local fishermen often reported seeing a sea monster as they traveled above the Monterey Canyon. Though descriptions varied, newspapers dubbed it “Bobo, the Old Man of the Bay.”

In 1938, Gus Canepa caught a strange fish off the Santa Cruz Wharf. The creature was first brought to the Museum of Natural History where it became a local celebrity. The original specimen ultimately went to be studied at the Smithsonian, who gifted this cast of this unique sea fish to the Museum. The specimen, a tapertail ribbonfish (Trachipterus fukuzakii), recently underwent conservation and is back on view in the Museum’s galleries.

Pernicious Pop Culture

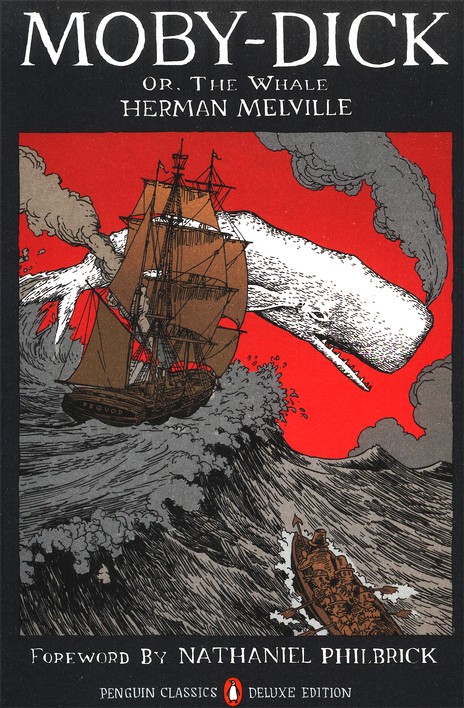

Herman Melville’s 1851 Moby Dick brought to life the horrors of whaling, painting the sperm whale as a dangerous foe. While 20th century science debunked many old sea monster tales, modern media continues to perpetuate and sensationalize fear of ocean creatures. Do any examples come to mind?

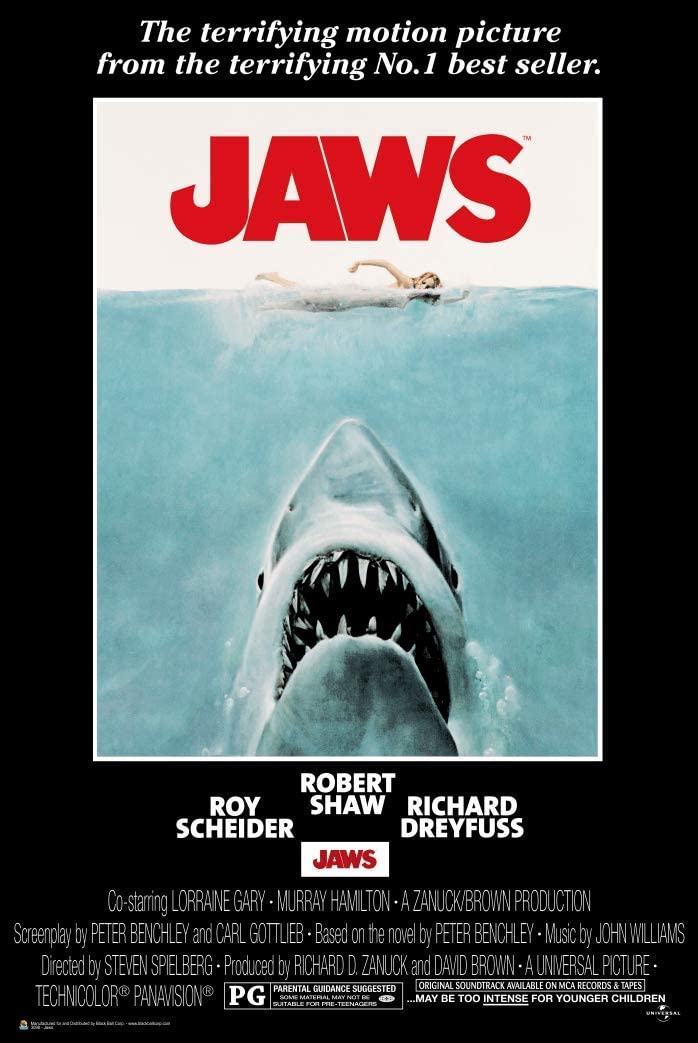

Movies like Jaws instilled a fear of sharks in many people, when in reality only about 6 people per year die from shark attacks throughout the world. Shark attacks are quick to make the news, but most bites are exploratory — the shark is determining what is in its habitat (and if it is food).

That Seafaring Life

Sea travel emerged in the ancient world as humans increasingly depended upon trade goods. It also allowed conquering nations to expand, colonize, and exploit the resources of newly “discovered” areas. Despite the riches that sea travel could bring, it was also full of potential hazards.

There are over 460 documented shipwrecks in the Monterey Bay area, many of which were caused by our thick coastal fog. In the 19th century, lighthouses were constructed along the Central Coast to warn passing ships away from the rocky coastline. Most people lost at sea, both then and now, succumb to hypothermia or drowning.

Even as navigational techniques advanced, seafaring was still full of frightening unknowns. Could you sail off the edge of the world? Or encounter a monster like those featured on medieval and renaissance maps?

In centuries past, one of the greatest dangers on the sea was likely other humans. Most Pacific Coast pirates attacked rich Spanish galleons out at sea and avoided plundering coastal communities. The exception to this was nearby Monterey, capital of 19th century Alta California. In 1818, privateer Hippolyte Bouchard attacked and burned the town, gaining control of the fort for six days.

Scientific Study of the Ocean

The field of oceanography explores the many facets of the ocean, from the geology of the ocean floor, to the dynamics of waves, and everything in between. Scientific study of the ocean is critical to our stewardship and understanding of the earth as a whole.

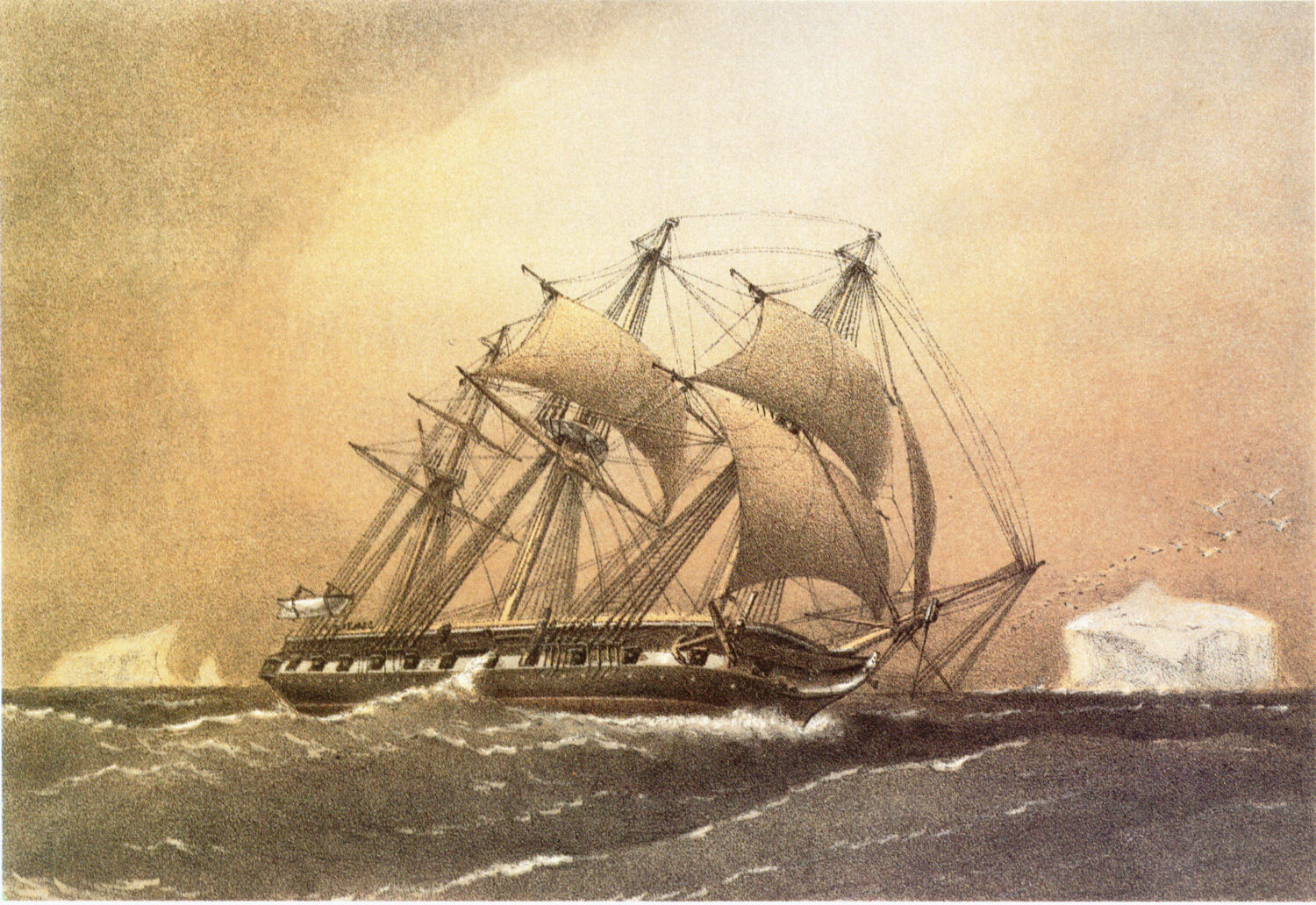

European naturalists aboard ships studied and documented marine life in the 18th Century, but the first truly scientific expedition took place in 1872, when the HMS Challenger embarked on a grand tour of the world. It covered 68,000 nautical miles and made discoveries that laid the foundation for modern oceanography.

Monterey Bay has a long history at the forefront of the study of ocean life. Ed Ricketts’ 1932 publication of Between Pacific Tides, which explored the ecology of intertidal life, set the stage for the decades to follow. Today, there are dozens of local organizations committed to ocean-related research, teaching, and policy.

Alien Worlds

Humans have only explored about 20% of the worlds’ oceans, and many of the most recent discoveries of deep sea creatures have come from the nearby Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute. MBARI uses robotics and other technology to explore depths of the ocean that no human could survive. Just off our coast the Monterey Canyon descends 2.5 miles, almost as deep as the Grand Canyon. Researchers at MBARI, with labs located at the mouth of the canyon, began mapping the seafloor here in 1998, and are tracking changes in the canyon’s shape and ecology over time.

As you descend into the ocean, the light, oxygen and temperature diminish while pressure increases. Many deep sea animals have adaptations that allow them to thrive in these conditions, though they may look strange to our eyes.

Humans as Monsters

While the ocean may seem threatening to us, humans are undoubtedly a major threat to the world’s largest ecosystem.

The ocean has absorbed about 90% of the excess heat caused by human-driven climate change thus far. A warming ocean has unparalleled cascading effects, including ice-melting, sea-level rise, ocean acidification, and loss of marine biodiversity. Plastic debris consumed by ocean inhabitants pose a great threat to the ecosystem. Whether it is microplastics being ingested by invertebrates, or bottle caps being swallowed by seabirds, the effects of plastic pollution in the food chain is detrimental.

Human activities in the last several hundred years have also drastically altered the soundscape below the surface of the ocean. These noises can travel huge distances underwater and disturb marine species like whales and dolphins, who rely on their supersensitive hearing to navigate.

Over 3 billion people depend upon the ocean for food, but unsustainable fishing practices can heavily damage ecosystems. In the early 1900s, the canning industry in the Monterey Bay devastated anchovy and sardine populations that marine mammals and seabirds depend upon for food. Only recently have populations begun to recover thanks for careful regulation and management by NOAA Fisheries in what is now a protected Marine Sanctuary.

From offshore oil spills to microplastics in the deep ocean, the impacts of humans are increasingly concerning. How can we help take better care of this important habitat, locally and globally?