Eggs can reveal a good deal about who laid them — hue, markings, shell shape and size can sometimes suggest the identity and even the health of the nester. But they can also show, as is the case with this month’s closeup, much more. Let’s take a close look at this month’s item: a selection of eggs from a larger collection of bird eggs, skins, nests, and mounted specimens gifted to our Museum’s founder in the early 20th century.

Over 100 years ago, on the 13th of April, 1904, Laura Hecox deeded her natural history collection to the City Of Santa Cruz. In documents detailing this gift, a note written in loopy cursive stands among them. It describes how Laura’s friend and fellow naturalist Ed Fiske gave these bird specimens to her for the very special occasion of the new museum.

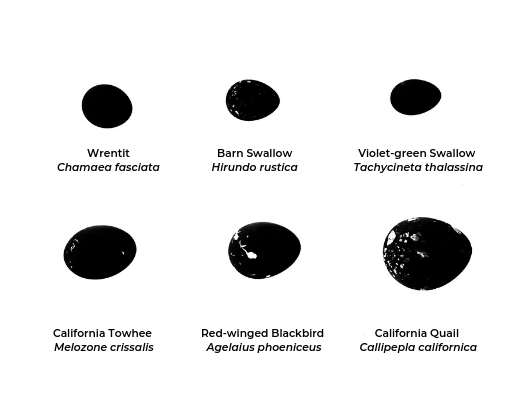

Among Fiske’s locally-gathered eggs, you see a snapshot of what avian species were present in late 19th century Santa Cruz. Looking at the labels, we find many birds we’re familiar with today. They span a few species, from a wrentit (C. fasciata) and violet-green swallow (T. thalassina), who produced the smallest eggs, to our state bird, the California quail (C. californica), with the largest egg among the collection.

A few years before Fiske made his gift, he and a collaborating naturalist, Richard McGregor, compiled a checklist of 154 bird species found within a 20-mile radius around Laura’s lighthouse. In this “Annotated List of the Land and Water Birds of Santa Cruz County, California,” published around 1892 as part of “Edward Sanford Harrison’s History of Santa Cruz County,” you can read the status and habits of each of these birds, some of whose eggs are on display this month. You can also read some of Fiske’s own collecting notes, as published in an 1885 volume of the publication “The Young Oologist” (“oology” was the term used to described the study of bird eggs during its heyday from the 1880s to the 1920s).

Fiske and McGregor were far from alone in their enthusiasm in collecting. Publications like “The Young Oologist” proliferated in their time, in addition to more scientific resources such as “The Journal of the Museum of Comparative Oology.” Museums amassed encyclopedic egg collections, including exotic and undescribed species, while amateur collectors tended to gather more local specimens.

Ultimately, the huge popularity of egg-collecting proved its undoing. Public outcry in the face of destructive collecting practices, for those taking eggs as well as decorative feathers, led to legal and cultural changes. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 is often considered the death knell of America’s egg-collecting fervor. It prohibits the collection of most birds, nests, and eggs except for scientific purposes.

Around the same time, the culture of birding shifted away from collecting birds and their parts to simply observing them. This was due in large part to conservation efforts of groups like the Audubon Society, as well as increased availability of tools like binoculars and cameras.

While eggs are no longer collected in the same way, the specimens that linger within museum walls offer a wealth of information. They answer questions in ornithology, including those of bird taxonomy, evolution, historical population distribution and breeding behavior. By showing researchers where nests were laid, what compounds have passed through a bird’s system and more, examination of eggs can inform research on climate change, environmental contamination, and conservation best practices.

Perhaps most infamously, a comparison of shell thickness between museum collections and contemporary specimens provided evidence that DDT was harming bird populations. This was crucial to the federal banning of DDT for agricultural use in 1972.

Our particular collection also illustrates the role small natural history collections can play within the larger scientific community. Like many naturalists of the day, Fiske donated specimens to more than one institution, one being the California Academy of Sciences. Tragically, the Academy’s collections were destroyed in the the 1906 earthquake and fire, in which only one specimen was salvaged.

Disasters like this emphasize the role a little natural history museum can play as a kind of biodiversity insurance. Because Fiske gifted specimens to his friend Laura Hecox, the natural history he captured — and all the information it carries — lives on into the 21st century.

Come visit us this month and browse Fiske’s eggs for yourself! If you’d like to dive deeper into the world of ornithology, the interactive birding data platform eBird is a great way to discover what birds are in your own backyard, and you can even make your own contributions. Nestwatch, too, is another tool that can help you better connect with local species while contributing data. The Santa Cruz Bird Club, who meets regularly at the Museum, also offers a wealth of resources to share with interested local birders.