The science of tying things together

Research appointments are the highlight of any given week in the collections department. Not only do we get to learn more about the ways our collections contribute to science, we get to see the process in action. Scientists and students bring their questions alongside various tools of the trade, from pencils to calipers to cameras. Paleontologist Chuck Powell travels with tupperwares of sand.

Chuck is a retired USGS scientist whose life’s work has focused on describing the geology and paleontology of the West Coast, with a special focus on Purisima Formation. His current project is a collaborative paper with four authors, including local fossil folks like Frank Perry and Wayne Thompson. The epic tome they are working on aims to describe all of the invertebrates of the Purisima Formation – a challenge given that new species are still being discovered. Leaving no specimen unturned, Chuck and his coauthors are visiting collections, both public and personal, across California.

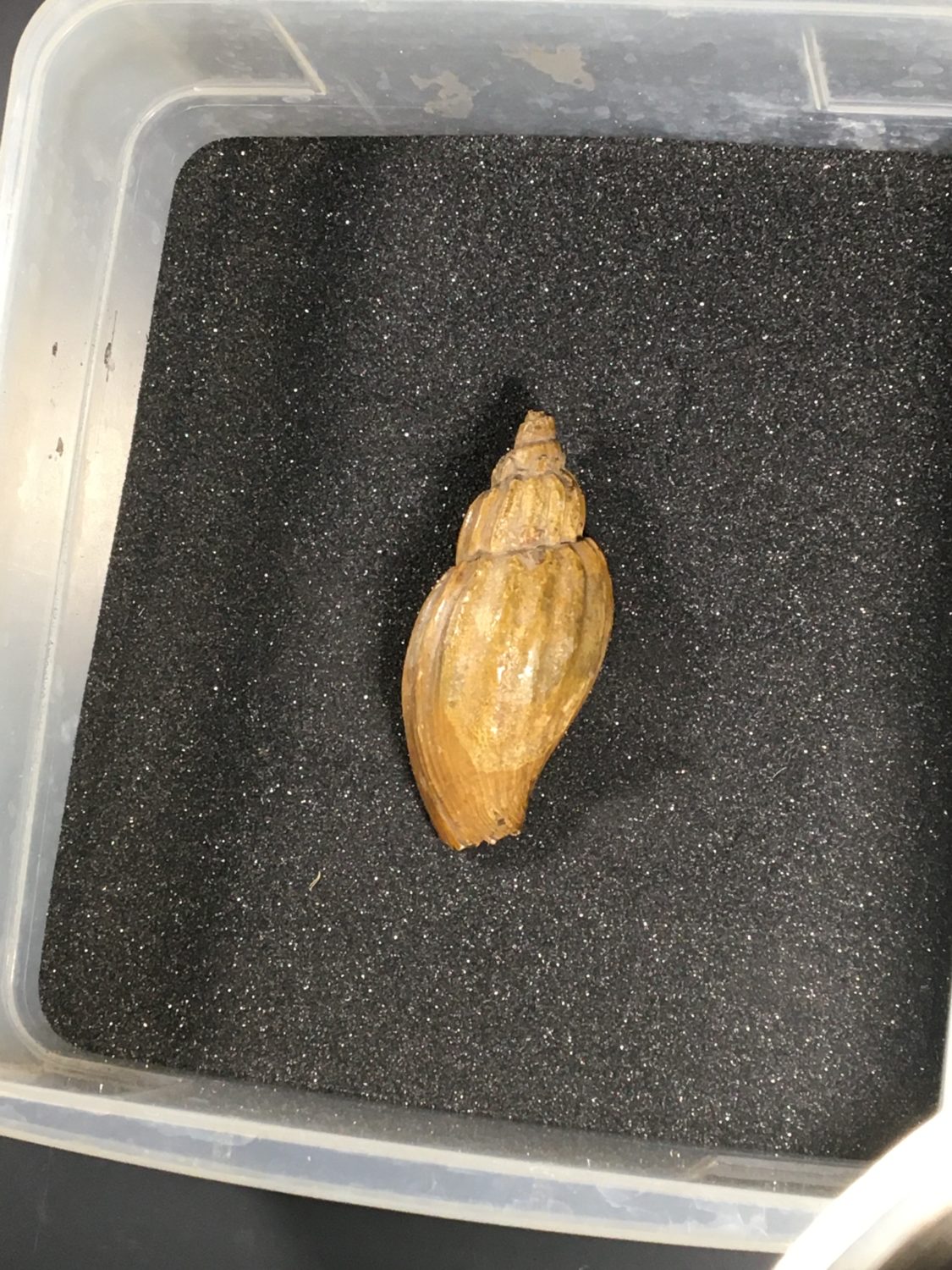

This kind of descriptive project takes an enormous effort and they have been at it for over 20 years already. It’s also an important part of taxonomy, or the branch of science concerned with the classification of organisms and their relationships. Digging into a drawer of ancient invertebrates, whether they are fossil ark clams or sand dollars, a taxonomist like Chuck starts by looking to confirm specimen identifications. One example of this is the pictured Miopleiona oregonensis specimen – while it has previously been described as being present in the Purisima, the three specimens in our collections are the first that Chuck has encountered, despite working on Purisima mollusks for decades and examining well over 700 collections.

Chuck Powell examines specimens during photography

Fossil Miopleiona oregonensis

However, he’s also looking to investigate and untangle our understanding of specimens with features that fall outside of the species identifications assigned to them — or even just to clear up confusion in the many names that a specimen can acquire over the years. For example, even after many west coast olivella snails (like Callianax biplicata, formally Olivella biplicata, whose shell has been commonly used by Indigenous peoples of the Central Coast for beadwork) were recognized as being in the genus Callianax, there was still a lot of confusion about which specimen names were valid. In 2020, Chuck and his coauthors pulled together the existing descriptions, evidence, and documentation for each name, clarifying its validity, and even providing a handy chart for identifying the four species in this genus we find on California beaches.

If that sounds like a lot of very detailed work to keep tabs on taxonomy – you’re right.

“People think taxonomists do it on purpose,” Chuck notes. ”That we change the names just to be ornery.” But that’s far from the reality. Taxonomists like Chuck are passionate about the way these updated names give us new information that helps tie things together — to open up relationships between organisms and their environment that we might have otherwise overlooked.

The photographs that accompany these revised descriptions become significant scientific evidence in this process. Any images published for this purpose elevate the status of the pictured specimen to something called a “hypotype”, which then requires special protocols and protections.

Photography is also where the sand comes in. In addition to bringing these fossils full circle to an environment similar to that in which they were grown, the black or white sand is the ideal backdrop. It provides soft but even support that is easily edited out in post production, while being very responsive to whatever adjustments are needed to show off the significant features, or morphology of the specimen.

Stay tuned for future updates on SCMNH specimens starring in paleontological publications. But don’t wait to dig further into the Purisima – USGS papers are freely available to the public, including these two dealing with the Purisima. Also available to the public this December are our geology and paleontology exhibits – outcropping briefly between our successful Seeds exhibit and our upcoming exhibition Pollinators: Keeping Company with Flowers.