Each spring as the surrounding landscape unfurls new life, we open The Art of Nature. This vibrant exhibit of local artists features as many different forms of nature as it does forms of science illustration. For this month’s Close-Up, we’re highlighting a method of recording nature found in our collections that makes a particular impression – gyotaku, the art of fish prints.

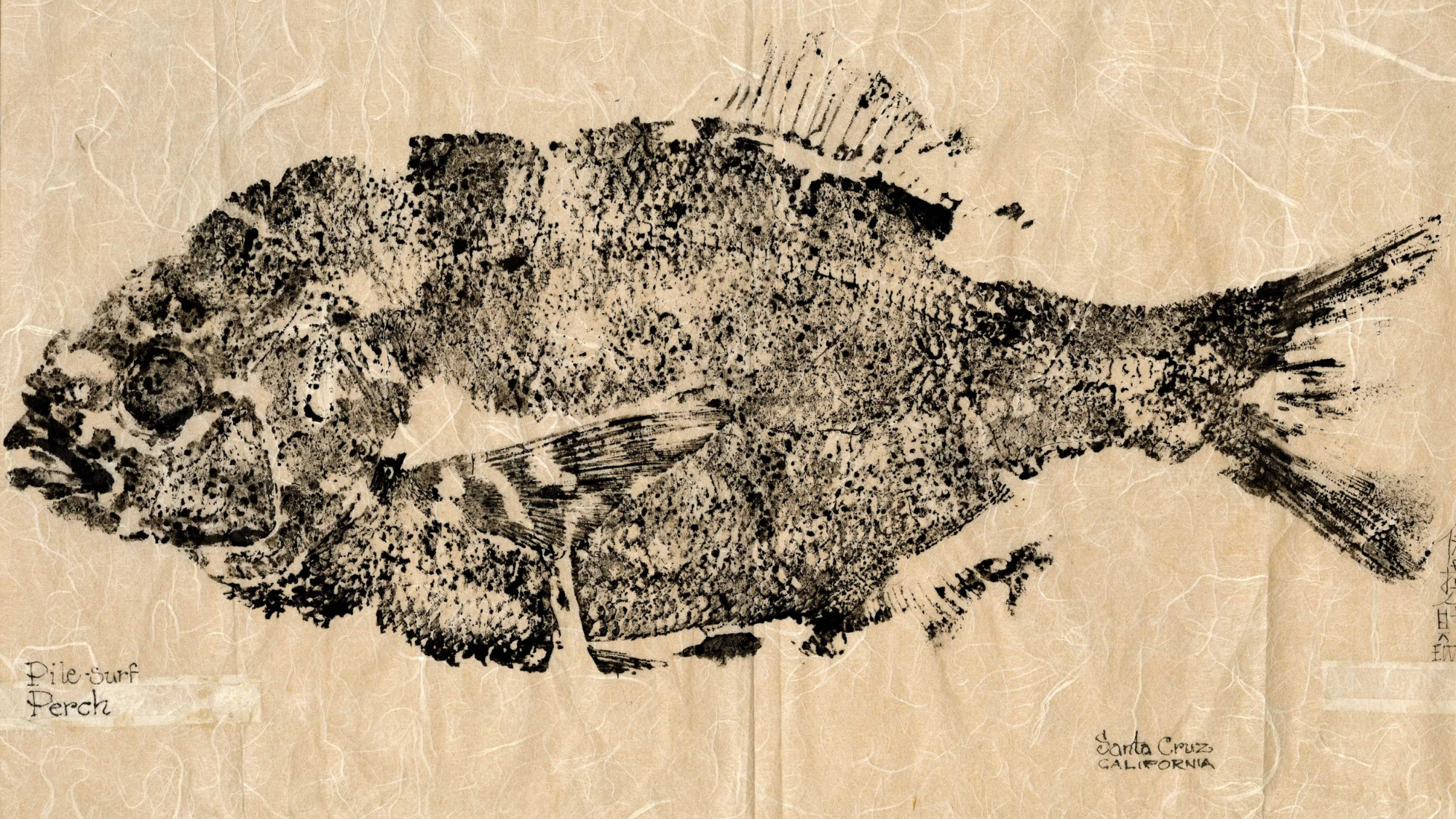

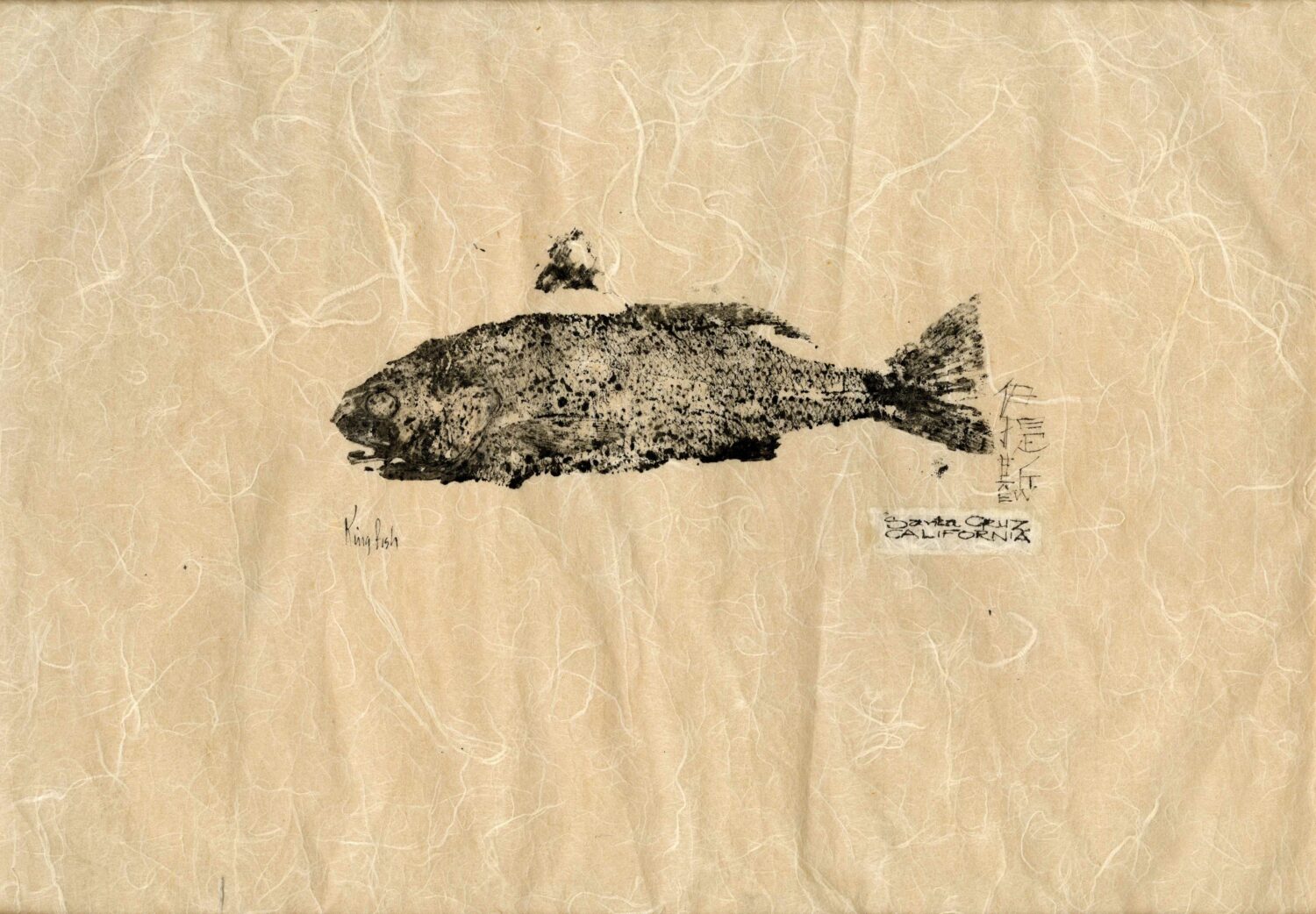

At its most traditional, this method relies on minimal supplies to make incredible works – producing fish prints that are both precise and dreamy, crisply capturing the anatomy of the specimens while simultaneously conveying the ethereal quality of the watery world in which they lived. You can see all these qualities in this dynamic print of a pile perch (Rhacochilus vacca) caught in the cabinets of our collections room. Scaly fish with a laterally compressed body, perch are great for gyotaku. More of the fish’s body is easily captured than with a more rounded fish body, as the printer trades the silvery sheen of the fish’s scales for the textured details of its skin and fins.

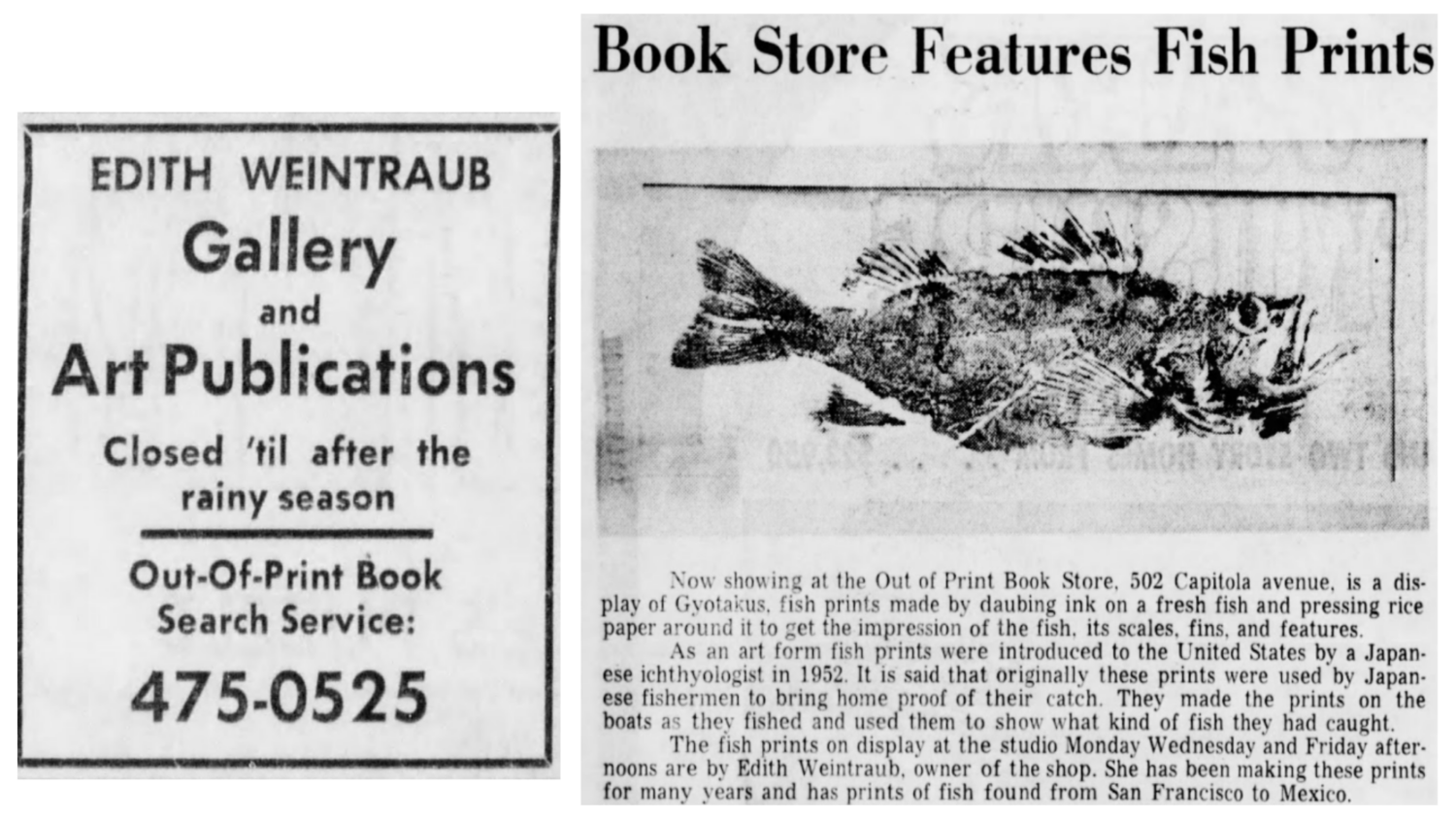

Printed in the 1960s by then Capitola-based artist Edith Weintraub, this perch print was made in the traditional “direct” method of gyotaku: Weintraub lightly daubed the perch with sumi ink, then delicately pressed Japanese rice paper onto the body and contours of the inked fish to produce a mirror image of the specimen. The fish was caught off the Santa Cruz pier, and this print may have been originally on display at Weintraub’s Out of Print Bookstore and gallery.

Edith appears to have been an early American adopter of the art – having made prints with Pacific coast fish for many years already by the time of her 1965 gallery showing. Gyotaku was first introduced in the US in the 1950s, by events like the American Museum of Natural History’s 1956 Gyotaku Exhibit and individual efforts like the introductory gyotaku book published by Yoshio Hiyama in 1964. Almost immediately it was seen as a natural fit for science illustration and natural history textbooks in the U.S. However, the art began almost a hundred years earlier – as a means by which Japanese fishermen in the 1860s could record their finest catch without the help of a camera.

As it flourished, new aspects of the craft were fleshed out. In addition to direct printing, other traditional methods include indirect printing, where you press the paper onto the fish and then ink the relief; and transfer printing, where you transfer the impression of the fish to a flexible surface, which is used to print onto another surface. Color can be used to accentuate the print, and eyes are often painted on after the initial printing. When all’s said and done, most artists/fisherman can still eat their fish – the entire process is traditionally non-toxic. And even while contemporary gyotaku has evolved to include new tools like computers, most of today’s artists (folks like Naoki Hayashi and Heather Fortner) make a point to talk about the ethics of how they collect their fish and how they are later eaten, composted, or returned to nature.

This is a trend even for folks who aren’t using fish – the term gyotaku is sometimes used to describe the inking and printing of other natural materials – even roadkill. This flexibility illuminates the technique’s ties to the general practice of nature printing – a centuries long tradition with a variety of global takes that continues to provide stunning images and contemporary insight into the relationship between humans and nature.

Meanwhile, contemporary gyotaku continues to keep the relationship between art, fish, and natural history firmly afloat. As recently as last year, artist Dwight Hwang, who makes gyotaku in the classical Japanese style, collaborated with the Natural History Museum of LA County to record an incredible catch: a female Pacific footballfish (Himantolophus sagamius), one of only thirty or so such specimens to have been found. Not only was this a rare and precious find that was important to document in many ways, the frightening forms of this creature also presented an incredible artistic opportunity. Hwang talks about how his approach to gyotaku, which he sometimes describes as a type of taxidermy, is grounded in a Japanese aesthetic of taking a subject and emphasizing the beauty in its imperfections.

To get a closer look at the perfect imperfections of Edith Weintraub’s local fish prints, and to get a feel for gyotaku yourself, register for our upcoming workshop with local printmakers Lucas Elmer and Janina A. Larenas.