A Cyclist’s Guide to the Wildflowers of Santa Cruz

Pedaling to petals, it’s almost too good to be true.

Add a little color to your bike ride with this mobile wildflower guide from the Santa Cruz Museum of Natural History. This flower field guide and bike route map will help you on your treasure hunt. Wildflowers can be fleeting so keep these routes on rotation to avoid missing the show!

Wildflower season varies from year-to-year, usually starting in March, picking up in April, and winding down in May. Some of these flowers pop-up early in the season, while others are late bloomers.

This guide was created in honor of Bike Month in partnership with Ecology Action. Learn more.

Easy | Moderate | Strenuous | Mountain Biking

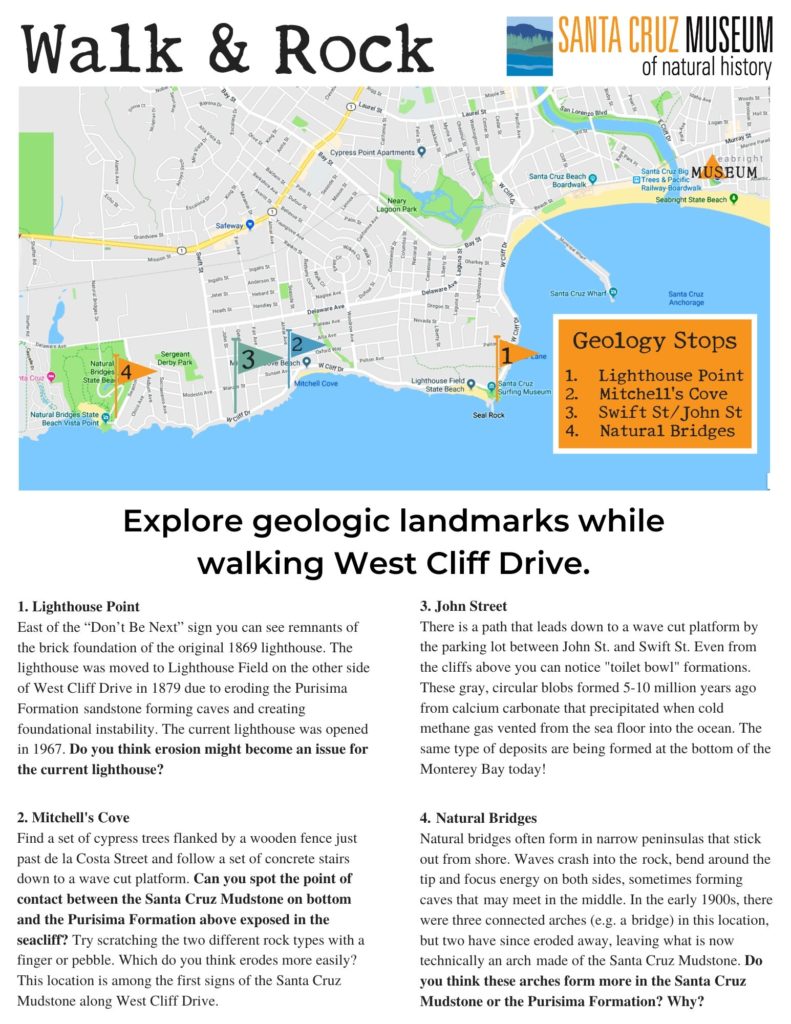

COASTAL CRUISING | Easy

This easy route takes you through some of the best wildflower viewing in the heart of town. You might think wildflowers belong in the wild, but with habitat loss such a huge threat to plant diversity, creating space for native plants in our urban areas is more important than ever.

Getting There

All Trails Route | Distance 7.05 mi | Elevation Gain 203 ft

This route cuts through town and along the coast, starting at Arana Gulch, then heading to the Santa Cruz Museum of Natural History, and ending at the UC Santa Cruz Coastal Science Campus. Then double back and see if you missed anything!

Santa Cruz Tarplant (Holocarpha macradenia)

Location: Arana Gulch

This rare and endangered plant endemic to Northern California is the reason we have Arana Gulch Open Space. The City manages the park in a way that promotes the success of this species. Adapted for disturbance historically common in coastal prairies, cows graze the landscape much like megafauna used to thousands of years ago.

Photo from Friends of Arana Gulch.

California Poppy Maritime Variety (Eschscholzia californica var. maritima)

Location: Santa Cruz Museum of Natural History

The Garden Learning Center at the Museum features several habitats. The front garden is a coastal prairie featuring our local variety of California poppy in abundance! Our maritime variety has a darker center with light edges, whereas the standard poppy is more orange throughout.

California Buttercup (Ranunculus californicus)

Location: Santa Cruz Museum of Natural History

These bright, shiny yellow flowers often bloom earlier than many other species, and will go to seed and return to a dormant state by early summer. Buttercups can be a nice source of nutrition and can be toasted or ground up and added to baked goods.

Common Self Heal (Prunella vulgarus)

Location: Santa Cruz Museum of Natural History

In addition to attracting pollinators, this edible plant has long been used as a remedy for a variety of ailments, including sore throats and muscle aches. Some of its other common names include heal-all, woundwort, heart-of-the-earth, carpenter’s herb, and brownwort.

Gumplant (Grindelia stricta)

Location: UC Santa Cruz Coastal Science Campus

In the early stages of blooming, the head of this yellow aster produces copious white exudate (i.e. goo). Indigenous cultures have traditionally used this exudate as an adhesive.

Western Blue Eyed Grass (Sisyrinchium bellum)

Location: UC Santa Cruz Coastal Science Campus

Actually a member of the iris plant family, blue-eyed grass produces deep purple flowers in late winter and early spring. The genus name means “pig snout”, referencing the sweet roots that were dug up by pigs in their native grasslands.

Explore our Guide to the Garden Learning Center

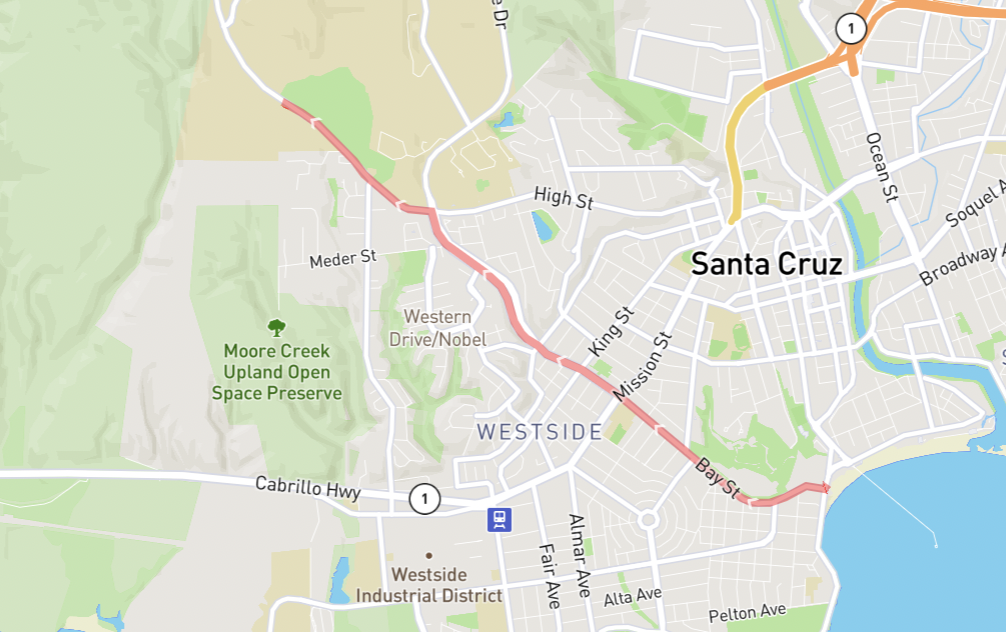

MEADOW MILES | Moderate

Sometimes you have to work a little for flowers, especially the really good ones. This route has you summiting one of our biggest in-town hills by biking up Bay St. towards campus. Part of the UC Santa Cruz Campus Natural Reserves, Mima Meadow is a coastal prairie featuring geologically interesting mima mounds and some of our most sought after flowers. Walk your bike through the paths to help protect the endangered Ohlone Tiger Beetle (Cicindela ohlone).

Getting There

All Trails Route | Distance 5.71 mi | Elevation Gain 427′

This route has you starting at the coast side of Bay St., taking it all the way to the top, then turning left on High St. and continuing on Empire Grade until you reach the closed gate to Mima Meadow on your left (just past the Arboretum). To get into the Meadow, you will need to use the steps in the fence at the fire road. Either lock your bike up at the Arboretum across the street, along the fence, or walk with it along the trails.

From here you can look down on your starting location along the Monterey Bay as you walk the trails. Stop by the UC Santa Cruz Arboretum and Neary Lagoon on your way back!

Monterey Mariposa Lily (Calochortus uniflorus)

The genus Calochortus contains some of our region’s most sought-after flowers. This rare species has grass-like leaves and upright flowers shaped like a bowl, which bees often rest in. Featured here is a longhorn bee (Melissodes sp.)

Yellow Mariposa Lily (Calochortus luteus)

Another member of the Calochortus genus, this California endemic flower is more widespread than C. uniflorus, but can still require a bit of a hunt. Conveniently, this species pops-up right near the gate to Mima Meadow. Turn right on the first trail you see and make sure you don’t discount every bright, big flower as a poppy!

White Brodiaea (Triteleia hyacinthina)

Also known as fool’s onion, this plant has an edible bulb, though it lacks the familiar onion smell.

Harlequin Lotus (Hosackia gracilis)

This rare plant belongs to the pea family and is unlike any plant you’re likely to find with its mix of sherbet colors. It’s thought to be a larval food plant of the Federally Endangered lotis blue butterfly (Lycaeides argyrognomon lotis).

Sky Lupine (Lupinus nanus)

Our region hosts many types of lupines and they can be challenging to tell apart. Even when not in bloom you can identify a lupine by its palmate leaves (five fingered like a hand).

Golden Brodiaea (Triteleia ixioides subsp. ixioides)

This cheerful yellow flower is in the same genus as the white broadiaea and also grows from a bulb.

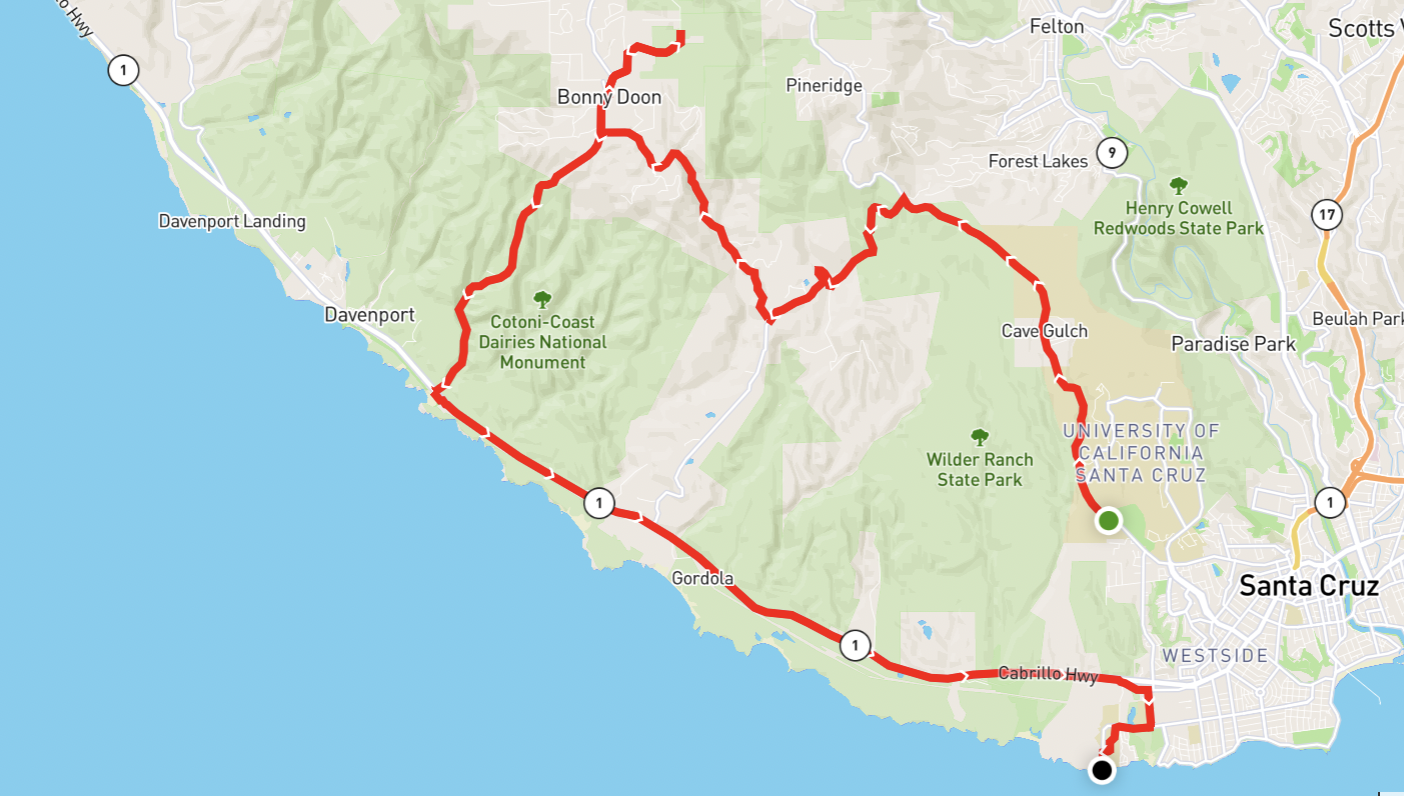

BONNY “DOOM” | Strenuous

The Bonny Doon Ecological Reserve is a spectacular location for exploring nature. An example of the rare Santa Cruz sandhills habitat, the soil is comprised of ancient seabed deposits and is very nutrient poor. For that reason, highly specialized plants grow here and nowhere else. It also burned partially in the CZU Lightning Complex fires, as well as during the Martin Fire of 2008.

Getting There

All Trails Route | Distance 24.85 mi | Elevation Gain 2,612 ft

From Mima Meadow, continue on Empire Grade. Turn left onto Smith Grade. You’ll meander through parts of the CZU Lightning Complex Burn Zone before reaching Bonny Doon Rd. Turn right and continue onto Pine Flat Rd. before taking a slight right onto Martin Rd. You’ll know you’re getting close when the habitat changes drastically, the sky opening up above you. Bike locking is a challenge, but you also don’t want to bring your bike along these trails.

When you’re done, double back down Bonny Doon Road to Highway 1 and take that back to the Coastal Science Campus for a relaxing view.

Ben Lomond Spineflower (Chorizanthe pungens var. hartwegiana)

You really have to see this flower in person to understand just how tiny it is. This rare member of the buckwheat family is found only in our local Santa Cruz sandhills habitat. You don’t have to travel far along the trail to find dense mats of this flower when in bloom.

Bush Poppy (Dendromecon rigida)

This shrub offers a pop of color to the Reserve when in bloom and can reach many feet high.

Ben Lomond Buckwheat (Eriogonum nudum var. decurrens)

Belonging to the same family as the spineflower, this variety of naked buckwheat is also rare and endemic to the Santa Cruz sandhills. Its leaves form dense basal rosettes and the tiny flowers sit atop long spindly stems.

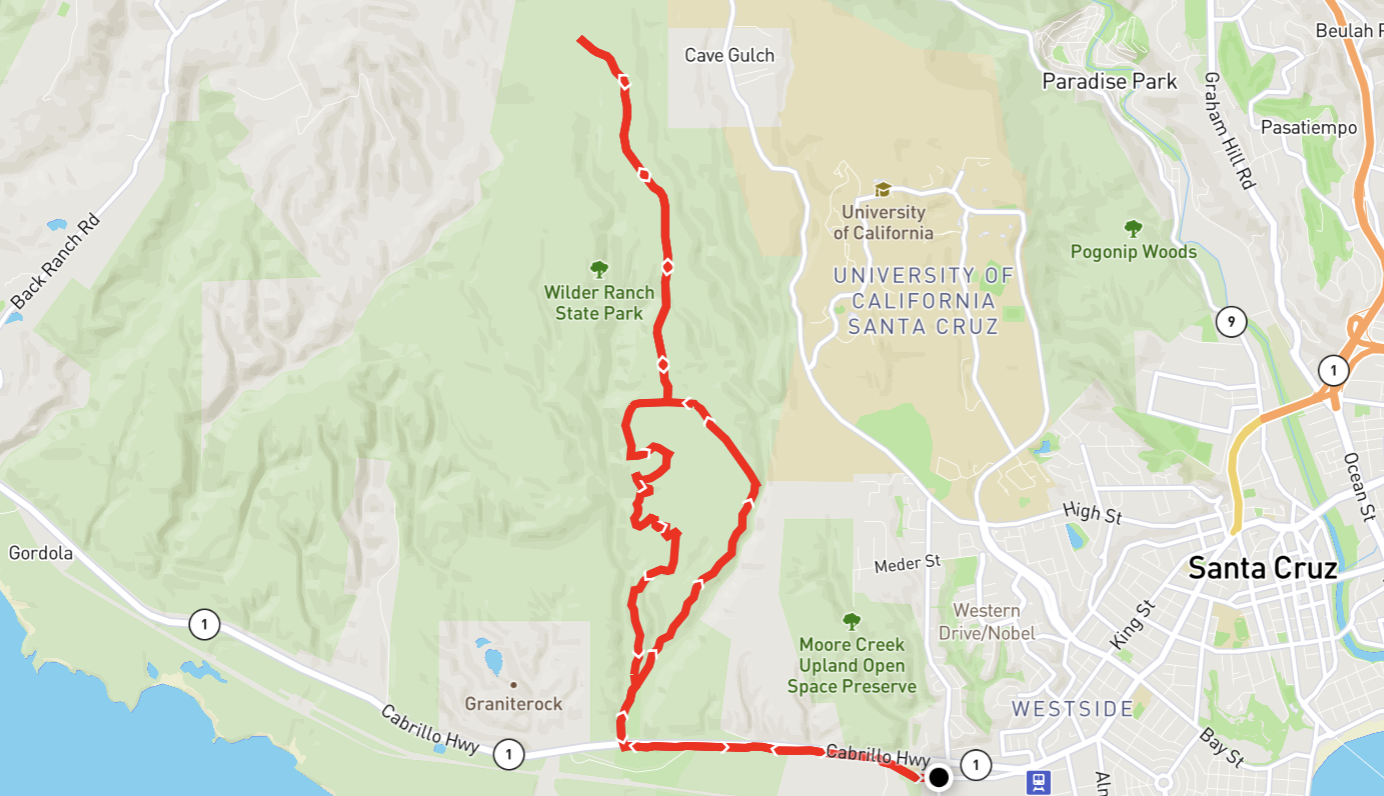

WILDERIN’ OUT | Mountain Biking

For those who prefer dirt to pavement, there’s great wildflower peeping along the trails of Wilder Ranch State Park. There’s not a bad trail for finding flowers, but this simple route takes you straight up towards the top of the park, passing through some of the best coastal prairie grasslands in the County. On the way back you’ll pass through redwood forest and woodland habitats.

Getting There

All Trails Route | Distance 11.75 mi | Elevation Gain 1,286 ft

This route takes you along the coastal bike path past invasive plants like wild radish, marigold, acacia, and french broom. When you get to the end of the trail, turn right and head up! You’ll take Engelman’s Loop to Long Meadow Trail, then double back and take the Wild Boar Trail for a change of scene and some fun twists and turns.

Common Fiddleneck (Amsinckia menziesii)

These early bloomers with their charmingly twisted tops will pop-up in droves. As the plant grows, the stem uncoils, and new flowers emerge, while the old flowers develop into seed pods along the lower part of the stem.

Western Heart’s Ease (Viola ocellata)

Wilder Ranch has a handful of native violets, ranging in colors from white to yellow. These are often found in the transitional zones from meadow to chaparral to redwood forest.

Fairy Lantern (Calochortus albus)

Another stunner from the genus Calochortus, this species has a different stature than C. uniflorus and C. luteus. Rather than a bowl shape, this species has flowers that drop like little lanterns. Find it on the edges of grassland and woodland habitats.

Purple Owl’s Clover (Castilleja exserta)

This species belongs to the genus Castilleja, which includes Indian paintbrushes. Like other related plants in the family, this is a hemiparasite which derives some of its nutrients directly from the roots of other plants.

Fremont’s Deathcamas (Toxicoscordion fremontii)

This perennial plant grows back year after year from bulbs underground. It’s referred to as deathcamas because all parts of the plant contain a toxic alkaloid that some consider more potent than strychnine.

There are so many more wildflowers to see in Santa Cruz than are included here. If you find something you don’t recognize, consider taking its picture and uploading it to iNaturalist. The app will suggest potential species and your observations will be recorded as biodiversity data, helping us better understand our natural world.